BIOS is on its way out but don’t shed

a tear. We explain how the flexible UEFI system brings computing up to date

If you’re buying a new PC, you may see

systems described as boasting a UEFI BIOS. If you’re building a computer from

scratch you may notice that some motherboards feature a UEFI BIOS, while other,

older models lack it. But what does UEFI mean, and is it worth paying extra for

it?

Why BIOS needs replacing

Anyone who has used a PC will be at least vaguely

familiar with the BIOS the Basic Input/Output System that’s stored in your PC’s

firmware and kicks in as soon as you turn on your PC. Before the operating

system loads, it’s the BIOS that handles the fundamental business of

enumerating which hardware is installed and applying basic settings such as CPU

frequencies and RAM timings. By accessing the BIOS’ built-in menu, you can

adjust various settings to make components run at different speeds, or

configure your PC to boot from a different disk.

UEFI

BIOS

Broadly speaking, the role of a PC BIOS

hasn’t changed in more than 20 years, and for most of that time it’s done a

satisfactory job. But as PC technology has advanced, more features that need

BIOS support have appeared, such as remote security management, temperature and

power monitoring, and processor extensions such as virtualization and Turbo

Boost.

Unfortunately, the BIOS was never designed

to be extended ad infinitum in this way. At heart, it’s a 16-bit system, with

very limited integration with the hardware and operating system, and it can

access a maximum of only 1MB of memory. It’s becoming increasingly difficult to

accommodate everything we expect from a modern computer within the old BIOS

framework. A new approach is needed.

The UEFI approach

Enter UEFI, the Unified Extensible Firmware

Interface. UEFI is a much more sophisticated approach to low level system

management. You can think of it as a miniature operating system that sits on

top of the motherboard’s firmware, rather than being squeezed inside it like a

PC BIOS. It’s therefore debatable whether or not it’s really meaningful to talk

about a “UEFI BIOS”.

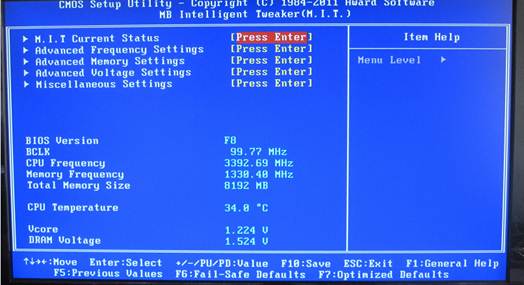

The

M.I.T. shows all the simple information a BIOS/UEFI should for an overclocker

at least – BIOS version, BCLK, CPU frequency, memory frequency, memory size,

CPU temperature, VCore and DRAM voltage.

This means that UEFI can be just as

powerful as a “real” OS. It can access all the memory installed in a system,

and make use of its own little disk storage space a sequestered area of onboard

flash storage or hard disk space called the EFI System Partition. New modules

can be easily added (hence “Extensible”); this includes device drivers for

motherboard components and external peripherals, so user options can be

presented in an attractive graphical front-end and controlled with the mouse.

On touchscreen hardware, it’s possible to change system settings by swiping and

tapping. It’s all a far cry from the clunky blue configuration screen of most

BIOS implementations.

What’s more, since UEFI is a software

environment, its high-level functions aren’t tied to any particular platform:

right now, UEFI works on ARM devices as well as regular PC hardware, and

there’s no reason it can’t be compiled for any other architecture that may come

along.

Who created UEFI?

UEFI has been under development for a lot

longer than you may realise. Chip giant Intel first started work on a

replacement for the classic PC BIOS back in 1998, to partner its nascent

Itanium platform. In 2002, its fruits were formalised as the Extensible

Firmware Interface (EFI).

Intel hasn’t kept the standard to itself,

however. Since 2005, the system has been managed and developed by a

cross-industry working group, including not only Intel but also AMD, Apple,

Dell, Lenovo and Microsoft. The organisation is called the Unified EFI Forum

hence the addition of the “U” to UEFI.

You might wonder why UEFI hasn’t caught on

sooner. In fact, the system in its various versions has been quietly gaining

momentum for a long time. In 2006, Apple switched all new Macintosh hardware

from PowerPC processors over to the Intel platform, and chose the original EFI

for its pre-boot firmware, a system it uses to this day.

Some Windows laptops have also started

using UEFI in the past few years, in order to provide friendlier and more

flexible pre-boot environments. This hasn’t attracted much attention, for the

simple reason that it makes no visible difference to most end users. And in the

cut-throat desktop market, PC motherboards have tended to stick with

traditional BIOS rather than invest in the more sophisticated UEFI. Until now,

that is.

UEFI and Windows 8

Historically, Windows hasn’t got along well

with UEFI hardware. In fact, back in 2006, when enthusiasts tried installing

Windows XP on the first Intel based iMacs, they were stymied precisely because

Windows XP the current version at that time has no ability to boot on an EFI

system. The situation was resolved only when Apple issued a firmware update

allowing Mac hardware to emulate a traditional BIOS (along with a driver pack

enabling Apple’s hardware to work in Windows).

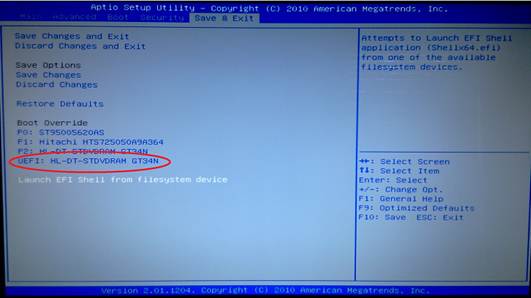

UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) - Install Windows 8 with

This shows the power of UEFI’s open ended

design. To date BIOS emulation has remained necessary, because Windows has

never had full support for UEFI.

This isn’t entirely Microsoft’s fault. For

technical reasons, a 32 bit operating system can boot only from 32 bit UEFI

firmware, while a 64-bit OS requires 64 bit firmware. This became a problem

when Microsoft introduced Windows Vista in both 32 and 64 bit flavours. Nobody

wanted to tell users they’d have to reprogram their motherboards to match their

Windows edition, and motherboard manufacturers didn’t want to support two

parallel versions of their UEFI firmware anyway.

So Microsoft settled on a compromise: UEFI

would be supported natively on 64-bit editions of Vista, while 32-bit editions

would continue to use a BIOS, either real or emulated. The same strategy was

adopted for Windows 7.

In Windows 8, however, the situation has

changed, and Microsoft has wholeheartedly embraced UEFI. Its certification

standards require that all new desktops, laptops and tablets sold with Windows

8, and bearing the Windows 8 sticker, must use a UEFI BIOS, to enable the use

of the UEFI Secure Boot feature, which we’ll discuss in more detail below. You

can still upgrade an older non-UEFI system to Windows 8, however you’ll simply

miss out on Secure Boot and a handful of other features, as we’ll describe

below.