We talk about the joy of mechanical

keyboards and what you need to get a good one

A typical review that I write here contains

around 3,000 characters (more if you include spaces), and on average I write

about 500 pages a year. That works out at around a quarter of a million words

and at least 1.5 million key presses. Factor in other publications and keyboard

use and we’re probably closer to 450,000 words and three million key presses,

which explains why after about six months of typical use the vowel key tops on

my keyboards are polished to the point that they’re all but unreadable.

The

Cherry MX Black key switch. Generally considered to be one of the best options

for those who are gamers rather than typists

However, it’s not just the keyboard that

takes a beating on my desk: what’s happening to my fingers? That’s a concern,

which is why I’ve taken the step of finding out what the best keyboards are and

what the technology behind them is.

Why So Mechanical?

I’ve noticed that lots of laptop makers

these days don’t care for mechanical keyboards, usually because they cost more,

but also the key travel on them makes the machine thicker. Some of these

designs, like the ones that Microsoft has offered on the Surface, use two

electrical contacts separated by a stiff membrane, which the pressure of your

finger brings together to complete the circuit.

The problem with this method is that there

is no obvious physical feedback when the key transitions between not pressed

and pressed, so to make sure you register a press you’re inclined to use more

force than is really needed.

That can cause damage to both the tendons

in the fingers, muscles and also the joints, which can eventually lead to

long-term damage and discomfort.

Cherry

Black MX Pink

The best keyboards, and the ones that allow

you to type rapidly and accurately, are mechanical ones, because they register

the key press before they’re fully depressed, which reduces the wear on you,

importantly.

The worst possible keyboards for comfort

are those on the screens of tablets, where you are effectively smashing the end

of your finger into a hard surface repeatedly. Those that input more than short

messages on their tablet need to seriously consider buying a Bluetooth keyboard

before they irreparably damage themselves.

Important Keyboard Knowledge

If advice on keyboards was as simple as

‘get a mechanical one’, then this would be a short article that wouldn’t be

remotely interesting. However, there are lots of variations within the making

of keyboards that can dictate if the design is right or not for you. For

starters, should you go for a USB or PS/2 type?

Cherry

G80-3000

Since it came along, USB has become the

standard for keyboards, as systems come with multiple USB ports and you can

have a desktop hub that makes your cabling much less complicated. Older systems

use the PS/2 connector, which is older than the hills, so which is best? PS/2,

amazingly.

The way that USB works means that the

system must poll the keyboard to find out if a key has been pressed and,

depending how busy the USB bus is, those polling actions might feasibly miss a

press. There is another USB mode which is interrupt driven, but the expense of

providing this means it’s never used on keyboards.

Alternatively, PS/2 connection is

inherently interrupt driven, so when the key is pressed a small CPU in the

keyboard sends a message to the main CPU to the effect that key ‘X’ was

pressed. That allows them to exhibit something called NKRO (N-Key Rollover). A

USB keyboard can only be polled for a set number of simultaneous keys being

pressed and any more are ignored. Most USB keyboards will only see four

different key presses at any one time, although they might also see one of the

Ctrl, Alt, Shift and the Windows command key in addition to the four ordinary

keys.

Better USB keyboards can be labelled at

6KRO, meaning they can poll six ordinary keys and they also can see four

special ‘modifier’ keys in addition. These are better, but they’ll never be as

good as an interrupt driven PS/2 keyboard that demonstrates proper N-Key

Rollover, which USB can’t achieve currently.

Ghosts In The Machine

Some keyboards are sold as anti-ghost, so

what’s that all about? There’s a situation that can happen when two keys are

pressed at exactly the same time, where the system generates a third key you

never pushed: the ghost key. This is rare, but it can happen.

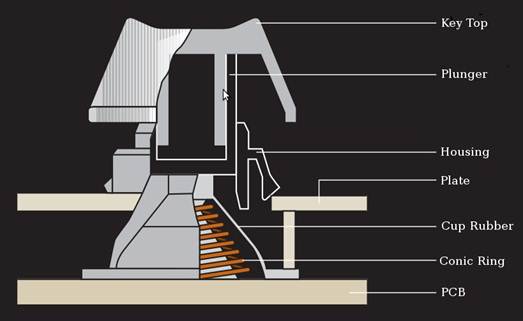

The

Topre switch. This radical switch design is a logical development of existing

switch designs to provide a better, cleaner action. However, the keyboards that

use it aren’t cheap

To stop this odd occurrence some keyboard

makers have instigated a form of software blocking that eliminates the extra

key press, but the downside of this is that it ignores that third press if it

really happens too, which is yet another problem.

This a limitation of the wiring matrix that

reads the keys and, as such, is difficult to combat entirely. The most common

place you’ll encounter ghosting or blocking is in gaming, rather than editing

text. As such, most of the keyboards with anti-ghosting tech are those designed

for this purpose. What they usually do is treat the WASD area of the keyboard

as special, so all simultaneous keys in this area are read, but it doesn’t mean

that the keyboard can handle any input combination without error.

The problem is more of an issue on USB

keyboards, because of the limitations on the number of keys that can be

simultaneously sensed, but even PS/2 ones aren’t entirely immune because of the

matrix on which the keys are electrically connected.

The Bounce

As a key is depressed, it eventually

triggers the switch underneath, and from the perspective of the computer the

contacts bounce to register multiple key presses. This is true irrespective of

what mechanism it is, and it’s something the system must cope with or typing would

be something of a nightmare. The way that this is handled is that once a key

press is recognised from a single key, then for a period of time further input

from that source is ignored until the key is considered ‘reset’. This is called

the ‘debounce’ and the better the keyboard the shorter this time is. A good

mechanical mechanism like one based on the Cherry MX switch has a debounce of

5ms, where a cheap keyboard might be a lot longer. The faster you’d like to

type, the shorter a debounce period you’ll need and want.

Filco

Majestouch

Mechanical keyboards always have shorter

bounces than those with rubber domes or other flattened designs, and it’s one

of the reasons that they’re better. However (and this is the catch), the

springs that create short bounce can also make these key actions noisy.

Time To Switch

When you start looking for keyboards you’ll

hopefully be told about exactly what switch the product you’re looking for

uses. The snag with this information is that most people don’t know a Cherry MX

Black from a Black Alps, unless they’re a hopeless geek like me. To help better

understand some of the nuances of key switch technology, I’ve created a chart

of some of the most common varieties (see bottom of page).

What’s important to know about these mechanisms

in respect to use is that switches like the Cherry MX Black are considered good

for gaming, because they’re not tactile and the tactile ones are generally

better for typing. Personally, I’d avoid the Alps design because it has a hard

ending to the press with no pre-activation, which can hurt you after extended

use. I’ve not tested them, but I’ve heard excellent things about Topre

switches, which depending on the specific keyboard can have a range of

activation forces, and they’re also very quiet (not being clicky).

There are others, but these are the ones

that are usually quoted, and it’s worth understanding what the difference is

between, say, a Cherry MX Blue and a Red. Understanding the switches can avoid

you ordering a keyboard that’s entirely unsuitable for how you intend to use

it.