The amount of debris hurtling around

in space is reaching alarming quantities and the risk of it falling to Earth

increasing

Back in August a giant Proton rocket failed

to reach its intended orbit and its passengers, a pair of DTH communication

satellites, were lost forever. In mid-October the BRIX-M upper stage of the

rocket exploded. By October 25 the authorities had calculated that the failure

added a worrying 500 pieces of larger space junk, and probably hundreds more

smaller pieces not observable on radar. This new batch of space junk has added

to the thousands of other parts hurtling around our planet and creasing very

real risks for rocket launches, and orbiting satellites such as the

International Space Station (ISS), Hubble Telescope and even GPS and other low

and mid-Earth orbiting craft.

A

NASA diagram of tracked space junk in Low Earth Orbit

By and large geostationary satellites are

immune from these threats given their extremely high orbits, but the risk of celestial

collision is extremely real for the rocket launches that have to penetrate this

‘junk cloud’ immediately after launch and while on their way to GEO orbit.

NASA reckons there are about 21,000 pieces

of space junk in orbit larger than 10cm (4in) across, and many, many more

pieces smaller than 10cm; in fact, NASA says there are “millions” of pieces

smaller than 1cm hurtling around. The danger of one screw or nut or tiny

segment of metal hurtling towards the ISS doesn’t bear thinking about. NASA says

that the ISS has frequently had to fire up its on-board engines in order to

“miss” potential space junk collisions. This uses up precious fuel and

potentially threatens scientific work that might be in progress when an

emergency is declared. The good news is that the threat is detected. The bad

news is that even a small flying missile, can arrive undetected and take off a

Solar Panel, or penetrate the ISS living quarters with devastating results.

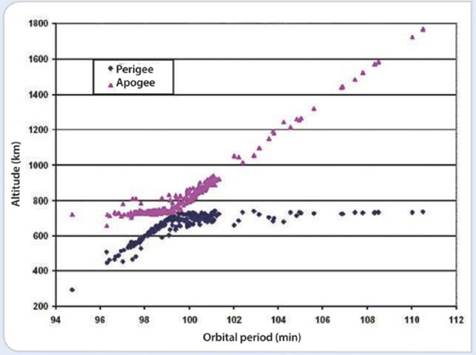

This

graph shows altitude and position of space caused by the deliberate destruction

of one of their satellites, measured in km above the Earth, and minutes

following the explosion.

Collision course

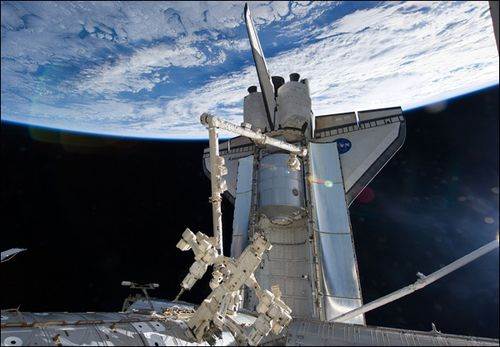

The International Space Station travels at

about 414 kilometers (257 miles) above the Earth and its living quarters and

principle technology segments are protected by a thin ‘meteor bumper’ or

Whipple Shield, designed to protect crew and components but not all parts of a

satellite can be protected in this way. The very thin shield works on the basis

that a micro-meteorite (or tiny piece of space junk) would hit the risk to the

actual craft. Solar panels, for example, are especially vulnerable.

Indeed, it isn’t just exploding rockets

that can do the damage. Back in 2007 China deliberately sent a rocket up to

destroy one of its own satellites!

Key to understanding the threat from space

junk is the ‘Kessler syndrome’, a formula that calculates the collision risk in

space (and even between planetary objects). The theory is simple enough: over

time all such parts diminish b falling to Earth or the planet they are orbiting

and burning up. The Donald Kessler work, initially focusing on the threats to

spacecraft by the Asteroid Belt in deep space, suggested that such risks to

damage could be mitigated and predicted. His theory has subsequently been

proven. Kessler’s work, and subsequent expert study, can predict with accuracy

the length of time it takes for these hundreds of pieces from a single impact

to decay and fall to Earth.

This is all well and good but the problem

is – as the October Proton launch proved – as fast as older object are decaying

we are creating new problems. Indeed, some experts now suggest that some parts

of our satellite orbital regions are hugely dangerous. By the end of the 1990s

it was calculated that of some 28,000 piece of largish space junk identified

the majority had decayed and fallen to Earth, leaving around 8,500 in orbit.

That number has been steadily increasing. By 2005 it stood at 13,000 objects.

By 2006 it had leapt to 19,000 objects because of a satellite collision in

space and by last year the number had grown to 22,000 items sufficiently large

to be tracked from Earth. And millions of piece too small to be tracked!

The risks are truly immense. NASA has

calculated that a small part, weighing no more than 1kg travelling at the not

unreasonable speed of 10km/s would have sufficient impact mass to totally

destroy a one tonne satellite. The USA’s National Academy of Sciences now

suggests that two bands are now extremely risky for satellite: the Low Earth

Orbit (LEO) band of 900-1,000kms, and the band around 1,500kms up in space.

As you rise further away from Earth and get

into GEO territory the risks get less, but are more difficult to track. For

example, from Earth we can only ‘measure’ by radar objects that are about one

meter across. And there’s a lot of junk up there still. One set of examples is

Russian RORSAT programmer, which saw satellites sent up in the 1970s and 1980s.

When they reached the end of their useful life most were sent high into a safe,

‘graveyard’ orbit. But some weren’t. And each of these satellites has on board

a risk that one of these will suffer a leak to its coolant reactor and release

its damaging material.

Into orbit

Scripps TV up for sale?

Scripps Networks, best known in the UK as a

50 percent owner of the ‘UKTV’ bouquet of channels, is said to be up for sale.

Scripps bought UK-based Travel Channel Int’l (for $107 million) earlier this

year. On the TV side of the business it has the record-fastest projected sales

growth forecast to 2015, and is among the top 13 US media companies.

MDA

are best known for the CanadArm retrieval crane

MDA can bud for SS/Loral

Canada’s MacDonald, Dettwiler and

associates (MDA) and Space Systems Loral (SS/L) have received anti-trust

approval to proceed with the take-over of SS/Loral by MDA. The $875 million

take-over was announced in June.

DTH increases in Brazil

DTH broadcasting in Brazil continues to

grow rapidly. Subscriber numbers are up more than 3.5 million over the past

year. September’s net growth topped 277,000 new subscribers, according to

Brazil’s National Telecommunications Agency (ANATEL), and taking the nation’s

DTH total (to September 30) to 15.1 million, and representing a 59.5 percentage

share. A year ago the share stood at 52.7 percent.

ITU condemns jamming middle East satellite

jamming has reached what one local broadcaster has described as “catastrophic”

proportions. While Eutelsat and Intelsat have legitimately removed troublesome

Iranian (IRIB) channels from their satellites, the jamming from within Iran and

affecting incoming satellite feeds continues. The BBC, France 24, Deutsche

Welle and the Voice of America are just some of the recently affected channels.

Intelsat drops IRIB

Intelsat has blocked Iran’s official

broadcast channels in Europe. Intelsat declined to confirm or deny an Iranian

report that it did so at the order of the US government. “Intelsat confirms

that we took IRIB (Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting) channels off the

satellite, “said Alexander Horwitz, a spokesman for the Washington-based

satellite operator.

Russia’s pay-TV revs up

Russia’s pay-TV market was worth $1136

million during the first nine months of the year, up 18.3 percent year-on-year.

The number of pay TV subscribers increased by 19.6 percent to 29.3 million,

meaning pay TV penetration now stands at 54 percent, up from 46 percent.