Working with virtual disks

By default, the New Virtual Machine wizard

creates each new VM with a dynamically expanding disk in the VHDX format. This

is a good general purpose setup, but depending on how you plan to use your VM,

it may not be the best choice.

For a start, VHDX is a new format,

introduced with Windows 8 and its Server 2012 counterpart. If you want your

virtual disk to work with older hosts and disk image management tools, you’ll

need to choose the established VHD format instead. This provides a slightly

lower level of fault tolerance, and supports disk images only up to 2TB in

size, but it should be ample for all but the most ambitious projects.

Consider disk type, too. A dynamically

expanding disk appears to the guest operating system as a fresh, independent

hard disk of a user specified size (the default is 127GB), but in reality it’s

simply a data file on your real hard disk. When created this data file takes up

a mere 4MB on your physical disk, and grows as needed up to your specified size

to accommodate the files that are written to it.

Windows

2012 Hyper-V VHD to VHDX Disk Conversion

Dynamically expanding storage saves space

(see Compacting and converting VHDs, below), but the trade-off is performance.

It takes time to dynamically allocate file space, and over time the disk file

is likely to end up becoming fragmented, further slowing things down. If you

can spare the space, you’ll likely see consistently smoother performance from a

fixed size disk, where the entire space of the disk is allocated when it’s

created.

If you want to get the very best

performance in your VM, a third option is to give it a dedicated physical hard

disk. This must be a non-removable drive, set offline in the host OS: it will

remain in this state while it’s being used by Hyper-V, ensuring the guest OS

remains fully isolated from your real system.

In certain cases you may not want to use a

dedicated disk or image at all, but to create what’s called a differencing

disk. Here, an existing disk image is chosen as the base image: to the guest

operating system it looks like a normal disk, but in reality any writes you

make are stored in a separate file, leaving the original image file unchanged.

If you want to base several VMs on the same operating system image, this can be

a space-efficient way to do it.

If you want to use one of these disk types

with your new VM, skip the default disk creation section of the New Virtual

Machine wizard by selecting “Attach a virtual hard disk later”. Then, to create

your new virtual disk, select New | Hard Disk in the Actions pane of the main

Hyper-V Manager and follow the wizard. Under “Configure Disk” you’ll notice the

additional option of copying the contents of a physical drive into your new

disk: this provides an easy way to virtualise a running system, perhaps so you

can try out software without affecting your real operating system.

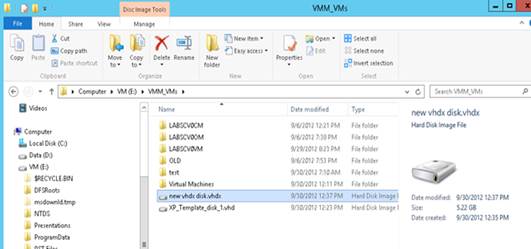

Once your virtual disk file has been

created, you can store it anywhere you want even on a network share or USB

stick. All you need to do now is attach it to your VM.

After

a couple of minutes, you have a .vhdx formatted drive from your original .vhd

drive.

Configuring virtual hardware

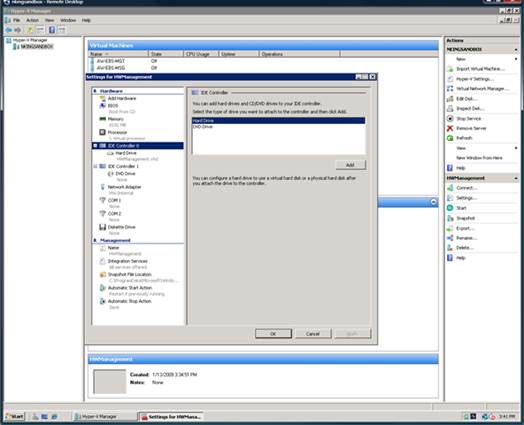

When you right click on a VM in the Virtual

Machines pane and select Settings, you’ll see a selection of hardware and

management options. Some of these relate to advanced features that you won’t

normally need to worry about, but feel free to browse: the interface provides

plenty of helpful contextual information explaining what the various settings

do.

It’s here that you attach virtual disks to

VMs. To do this, click on one of the virtual IDE or SCSI controllers in the

left-hand list, ensure Hard Drive is selected from the list of disk types, then

click Add and select the disk file you want to use.

You can also connect a VM to a virtual

switch from this interface: simply click on Network Adapter and select your

switch from the dropdown.

While you’re here, it may be worth looking

at the BIOS options, which allow you to set boot priorities if you have more

than one virtual disk attached. Memory options let you assign RAM to your VM

and prioritise how memory should be dynamically allocated if it becomes low.

Processor options let you control how many cores and how much processor power

your VM can use useful if you want to ensure your host OS remains responsive.

You’ll also find a compatibility setting here, which restricts the processor to

using features that work across a wide range of physical hardware, so the VM

can be hosted by multiple different computers.

Installing the OS

Virtual hard disks are created blank, so

unless you’ve copied the content of an existing physical drive, the first thing

you’ll need to do is install an operating system on your virtual machine. If

you allowed the New Virtual Machine wizard to create a virtual hard disk,

you’ll have had the option of mounting a physical bootable DVD, or an ISO file,

from which to install your operating system.

You can also configure this from your VM’s

Settings window: select an IDE controller, then choose DVD drive as your disk

type. Click Add, then choose either a physical drive installed in your host OS

or an ISO image file to mount as a DVD drive in your VM. Job done.

Installing

the OS

Remember: you need a licence to install an

operating system in a VM, just as you do for physical hardware. Legally, a

retail copy of Windows 7 or 8 can be used on only one machine at once be it

physical or virtual so you’ll need a product key that isn’t being used anywhere

else to legitimise your virtual installation. If your OS is an OEM edition then

you have even less flexibility: these licences are valid only for the first

system upon which the OS is installed, so if your OEM copy of Windows has ever

been used on a physical PC, you’re not permitted to install it in a VM at all.

Unless you have some spare Windows licences

to hand, therefore, you might prefer to use one of Microsoft’s freely available

virtual Windows environments (mentioned above) or simply install a Linux

distribution, such as Ubuntu, available free from www.ubuntu.com.