Wintel has ruled the PC world for

almost a decade now, but seems to have lost its footing. Is it too late for it

to scramble back to the top?

Microsoft (Windows) and Intel have been

defining the computing experience of the world for well over a decade and the

word “Wintel” is now synonymous with the PC the way Google is with the

internet. There was a time when Wintel commanded over 90 percent of the global

PC market, but times have changed and with the rise of the smartphone/phablet/tablet

and the promise of portability and power, the true definition of personal

computing has been blurred to include all these fancy new “computational

devices.” In this new world, it is the AAA that rule, Android, Apple and ARM,

with the all-powerful Wintel now being relegated to a more humble 20 percent

market share (http://dgit.in/ULwHN9). With Microsoft branching out to ARM, and

Intel unable to compete in the mobile computing space, is the era of Wintel

finally over? What is ARM exactly and why is Intel, the largest chip

manufacturer in the world, unable to compete? To understand this we need to

understand the way these CPUs process data and why this is so important to us.

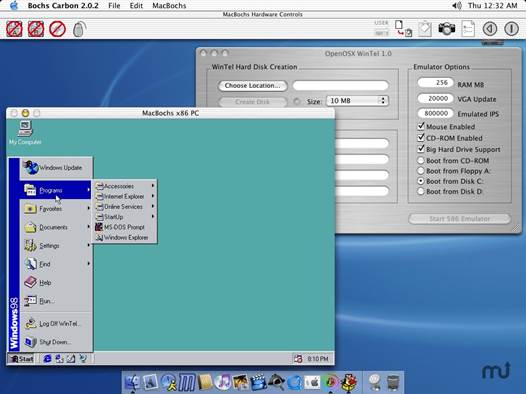

Wintel

3.0 for Mac

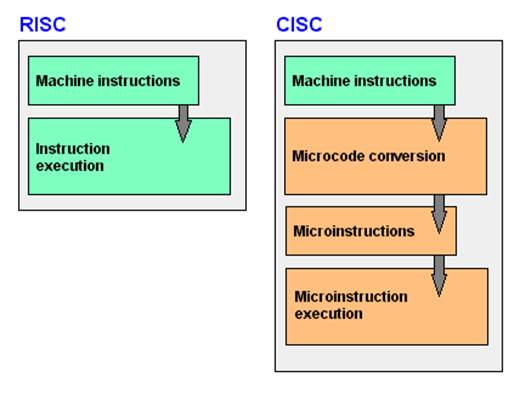

Intel chips are based on a CISC (Complex

Instruction Set Computing) architecture that essentially allows the CPU to

process multiple low-level instructions simultaneously, which also reduces the

number of instructions required to complete a task; thus simplifying the

programmer’s (and compiler’s) job.

Brainless monkeys

RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computing),

an architecture used by ARM, is the exact opposite of CISC where only one

instruction is processed at a time, in sequence. This increases the compiler’s

workload as each task would have to be split into multiple steps. This would be

better explained with a simple analogy; if someone were to tell you to get them

some water, you would just go to the water source, fill a glass with water and

bring it back to that person. This is CISC where you are the processor and the

“someone” is the OS or compiler. In RISC mode, you would need to be given

specific instructions; turn 180 degrees, walk 5 meters, turn left 90 degrees,

walk 7 meters, and so on. In this situation, you, as a CPU, don’t need to think

too much and the instructions can be as easily followed by a person as well as

a somewhat well-trained monkey. If the instructions are given at the right

time, there wouldn’t even be a time lag between the two methods of operation

and there is not much brain power involved (no offence to monkeys). The problem

arises when, say, the glass is not there at the location you specified, the

monkey would not know what to do next and may not even be able to tell you

that. In computing terms what this means is that the program will just get

stuck and/or will return an incorrect result. Current processors do have

methods to prevent such a thing from happening. The main advantages of RISC can

be summed up in the following points:

RISC

(Reduced Instruction Set Computing), an architecture used by ARM, is the exact

opposite of CISC where only one instruction is processed at a time, in

sequence.

·

A simpler architecture, meaning fewer

transistors and it’s hence, cheaper to produce.

·

Very high efficiency per clock (if the code is

compiled correctly) and per watt, translating to lower operating temperatures.

·

Lower power consumption because of fewer

“components” and higher efficiency.

The end of Geekdom

As can be seen from the advantages of RISC

listed above, this architecture is ideal for mobile devices because it provides

stellar battery life (compared to CISC processors) and negligible heat (again,

only in comparison to CISC). Comparatively, CISC architecture such as Intel’s

x86 (except Atom) is leagues ahead of any ARM processor in terms of sheer

power. The problem here is that most people don’t need that much power. What

does the average person’s computing usage involve? Nothing more than Facebook,

a bit of YouTube, some Instagraming and maybe a bit of mild video editing. Most

work is also something that just involves office suites and e-mails. You don’t

need a quad-core i7 to do that. In fact, you don’t even need an i3. An

ARM-based tablet or phone can do that much admirably while still giving you

portability and stellar battery life. Nowadays building your own computer is

almost considered to be the equivalent of building your own table or chair.

Computing is such an integral part of our lives that it has just been taken for

granted. You might think that this only applies to first world countries but

you’d be wrong. More people have smartphones than PCs and internet access is

just a SIM card away. Almost everyone knows how to operate a phone, send an

email and browse the web. Where is Windows or Intel here? They just don’t

matter anymore. Internet Explorer 6 was the most popular browser for so long,

despite being so flawed and people still used it and not just because they

didn’t know any better. They didn’t know any better but it was more the fact

that the prospect of using a PC (and Windows) was such a daunting task that

they just preferred to stick to something they knew rather than try something

new which might create a whole pile of other unknown issues.

a

quad-core i7

It is this situation that Apple managed to

take advantage of when it launched the iPad. People were comfortable with it, they

never really felt that they could damage the OS. They got a good device, a good

browser, it could access the internet and it seemed way better than the Windows

experience that they had been used to for so long. There was no more messing

around with settings, no installing scary applications that might install a

“virus”. Curated content and a curated experience became the norm and it was

enough. The geeks did fret and fume about it, but Google lent a hand and

Android filled the gap.

Microsoft (and Intel), for whatever reason,

remained completely oblivious to this space and while they did ultimately catch

on, they were far too late. The products they released just seemed slapped

together and while they had the right idea, they were too late and tried too

hard to adapt in too short a time period.