We investigate who’s keeping tabs on

your online activities and what you can do about it?

The Internet us undoubtedly one of the

great inventions of the modern age. Never have so many people had access to so

much free information. Never have so many people had access to so much free

information, while project such as Wikipedia have shown what can be achieved

when the power of the masses is harnessed to achieve a common goal.

Whereas previous generations turned to the

Encyclopaedia Britannica in their quest for knowledge, provided that they were

fortunate enough to own the multi-volume respository, people now access its

online contemporaries: Google, Wikipedia, even Twitter. The Encyclopaedia

Britannica is itself available in subscription-based online form, and the

ability to frequently update the information it provides means it’s now more

reliable as a research tool.

The

Internet us undoubtedly one of the great inventions of the modern age

Social media has also grown at a phenomenal

rate, and with it transformed our ability to communicate on a wider scale.

Tracking down old friends and colleagues is no longer the preserve of amateur

detectives with a battered book of phone numbers and addresses circa-1993;

today, more often than not, you can simply log into Facebook and type in their

name.

We have available to us an incredible

number of free online services – Skype, Gmail, Google Docs, Twitter, Facebook,

Dropbox… many have become an essential part of our daily lives. For consumers,

this truly is a golden age for technology. But what do the sites and services

themselves get out of it?

The hidden costs of free services

We know that business need to make money to

even exist, let alone thrive. Google’s data centres are famously home to

thousands of computers, each holding fragments of the world wide web. Around 48

hours of video is uploaded to YouTube every minutes, which translates to eight

countries, with some 900 million monthly active user accounts.

We don’t pay to search, upload badly taken

photographs of schools plays, or watch little pandas sneezing, yet Google is

one of the most profitable companies in the world and Facebook is valued at

$99bn.

We

don’t pay to search, upload badly taken photographs of schools plays, or watch

little pandas sneezing

So how do they do it? What’s the secret to

their success? Technical brilliance aside, the answer is very simple: you. Or

more accurately, what you like and what you might want to buy.

The free services we access on a daily

basis are watching us where we go, what we do and using that information to

provide their advertised, or even other companies’ advertisers, with profiles

that enable them to sell to us more effectively and increase the chance that we

will click the ‘Add to basket’ button.

Remember that old phrase: if you’re not

paying for it, you’re not the customer; you’re the product being sold.

Me and my shadow

During his recent TED talk, ‘Tracking the

Trackers’, Mozilla CEO Gary Kovacs discussed the idea of behaviour tacking and

its proliferation across the web. In essence, when you visit a website a cookie

is created in your browser that allows the site to know you are there and help

it to perform basic tasks, such as maintaining the contents of your shopping

basket while you continue browsing the site.

Cookies can also gather information on the

pages you visit and items on which you click, so that the content you’re

offered is more relevant. Generally, cookies enhance the browsing experience

(try disabling them in your browser’s privacy settings to see just how clunky

the web can be) and often save you from having to log in or set preferences

each time you visit a site. All this is perfectly acceptable, helpful even; more

worrying is the fact the behaviour Kovacs discussed can continue after you

leave the site.

You might expect a site to retain the

information on the cookie for the duration of your stay, then for that cookie

to become insert when you leave. This isn’t always the case. Third-party

cookies can continue watching your movements, sometimes across several sites to

none of which you have given your consent.

The effects are easy to observe – in fact,

you’ve probably already seen them. Search for details on, say, Batman, and it

won’t be long until related products begin appearing in the advertisements on

other sites you visit, sometimes with unnerving accuracy.

This is made possible by the relationships

between the host sites and online advertising companies, such as

scorecardresearch.com, tribalfusion.com and doubleclick.net. The idea is to

provide you with a tailored experience, and tempt you to make a purchase.

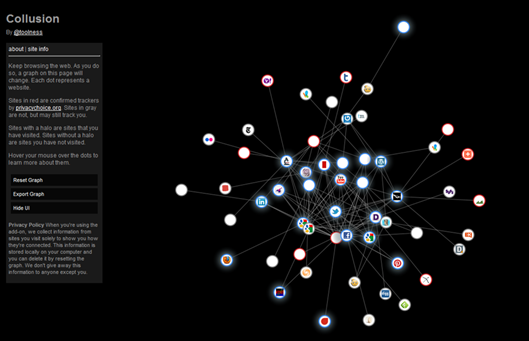

Collusion

displays tracking cookies in a similar fashion to cells under a microscope

Revenue generated from these advertisements

is staggering. In 2011, Google was reported to have made $55.5bn, with nearly

all of this derived through AdWords and AdSense. Facebook also ranked in a

respectable $5.55bn, with 85 percent the profits of advertising. It’s no surprise

that companies are keen to know what we want to buy, and the most effective way

to place those products in front of us.

The idea of our habits monitored especially

by those who would hope to seek profit, is an uncomfortable truth that

accompanies our heavily interconnected online world. Gary Kovacs puts in very

eloquently: “We are like Hansel and Gretel, leaving breadcrumbs of our personal

information everywhere we travel through the digital woods.”

To observe tracking, Mozilla has developed

the Collusion Project, available as a Firefox plug-in, which displays tracking

cookies in a similar fashion to cells under a microscope. It doesn’t take long

for those cells to multiply.

“On a technical level, Collusion plugs into

your browser and watches all these requests to websites and third parties

involving cookies,” explains Mozilla’s Ryan Merkley. “Firefox already makes a

record of some of this (your browsing history) and Collusion is recording a

little bit more so it can be drawn on your screen. The more you browse, the

more Firefox and Collusion accumulate about relationships, and your graph gets

larger.”

That’s something of an understatement. In

our own experiment we cleared the browser history, installed Collusion, then

visited some of our bookmarked sites: The Guardian, Football365, Facebook,

Twitter and a few others. After viewing just nine sites, and spending less than

20 minutes online, we had been tracked by third-five cookies.

In another test we reset the browser and

visited the site of a popular high-street videogame retailer; the results were

startling. Just by landing on the home page we saw 11 third-party links appear

on our Collusion graph. Ryan Merkley’s initial experience of the application

was equally concerning.

“I first tried Collusion when one of our

engineers hared an early proof of concept,” he says. “I was shocked at the

number of trackers and, most of all, by the number of times a very small group

of trackers showed up. Those few trackers know more about my combined browsing

habits than any website ever would. it made me want to know how they use that

data, and have a tool to decide for myself whether they would be able to

collect my data at all.”