The law

It response to the ever-increasing issues

surrounding privacy, EU Law has put in place the e-Privacy Directive. This

states that no user should be tracked without their consent. You may have

noticed the pop-up boxes that now appear at the top of websites announcing that

they use cookies; they will either require you to click to accept this or, in

some cases, state that by continuing to use the site you are giving your

consent.

The short explanations very rarely mention

anything about third-party cookies, and often appear only the first time you

visit the site. If you fail to spot the notifications or think you’ll have a

look when you have more time on your hands, you will continue to be tracked as

before.

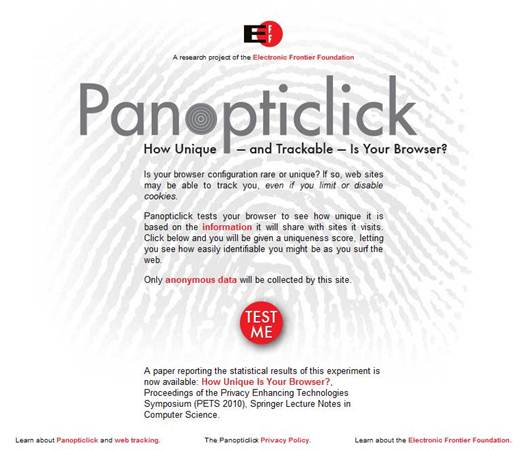

Panopticlick

allows visitors to its site to establish whether their PC is trackable

To learn how the site uses cookies, you

normally have to click the privacy polices link highlighted in the message.

Sometimes you can select which cookies using your web browser’s private or

‘Incognito’ mode, which stop sites from adding permanent cookies or tracking

your web history.

Another sensible move is to visit the

security settings in your browser of choice and look for the ‘Do Not Track’ or

‘Do not allow third-party cookies’ option. Plug-ins such as Ghostery are

available for most browsers and offer an enhanced level of security, while

Internet Explorer users can use ‘Tracking Protection Lists’ to prevent know

offending sites to place cookies on their machine.

Sadly, even these settings can be overcome

by something called device fingerprinting. Your system is made up of lots of

small details such as the browser type, operating system, plug-ins, and even

system fonts that can be scanned and interrogated to reveal an individual digital

fingerprint that identifies your machine on the web.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation

(eff.org) is a digital rights group that campaigns against invasions of civil

liberties. To illustrate the effectiveness of device fingerprinting, it set up

the Panopticlick website. Here, users are able to measure how easily

identifiable their system are.

We tested our road-worn laptop and were

slightly unnerved to discover that, out of the 2,287,979 users that had scanned

their machines on the site, ours was unique and therefore trackable.

Some would agree that the ability for

companies to track our interests is a fair price to pay for the free services

we receive. After all, websites are only offering opportunities for advertisers

to pitch their products to us. Television, radio and cinema all do the same

thing, and use demographic profiling to promote certain products at calculated

times hence all the beer and crisp commercials during football coverage.

No-one forces us to use networks, and there

are alternatives to all Google’s online offerings. But it is such a bad thing

that we are being watched what have you got to hide? Well, that all depends on

who is doing the watching, and why.

The spying game

Currently negotiating its way through

parliament is the government’s Communications Data Bill, or the ‘Snooping

Bill’, as opponents prefer have termed it. This radical restructuring of

British law would force ISPs to retain communications data for all email, web

browsing and even mobile phone use in the UK.

The authorities would then be able to

access the information in a limited capacity at any time, or in its entirely

when granted a warrant. The government is also claiming that it will be able to

decode SSL encryption as part of the process..

For a nation that’s already heralded as the

most surveillance heavy country in the world, this might seem to many a step

too far. What some privacy campaigners see as the real problem, though, isn’t

necessarily the government prying into our digital lives (although that’s

obviously a concern that they are highly), but rather the fact so much

information about us will be collected and stored, with potentially dangerous

consequences.

Most of us would agree that although we

might not always like how our elected officials behave, we still have a

reasonably accountable government. We could also agree that while companies

such as Facebook and Google make money from us in a less-than-transparent

manner, they too are not out to harm us. But the fact that all are intent on

assembling hugely detailed data sets poses a problem if that information is

ever used by organisations that are not so benign.

In January 2010 Google announced that it

had been the victim of a sophisticated cyberattack originating in China. The

hackers had gone after the email addresses of human rights activists,

journalists, and some senior US officials. Wikileaks then released leaked cable

communications that suggested a senior member of the Chinese Politburo had been

involved in the attacks. Some reports suggested that the motivates behind the

attack were to identify and locate political dissidents who were speaking out

against the government’s human rights records.

In

January 2010 Google announced that it had been the victim of a sophisticated

cyberattack originating in China

The following year saw the rise of the

‘Hacktivist’. Modern day protestors against abuses of civil liberties or

digital freedom.

Among the high profile victims of groups

such as Anonymous and LulzSec and Sony, the US Bureau of Justice, our own Ministry

of Justice, the Home Office, several Chinese government sites and even the

Vatican... twice. In fact, Verizon released figures reporting that more than

100 million users’ data had been compromised by the Hacktivist groups in the

past year.

Although the motivation behind the

Hacktivists efforts are generally for the greater good, the ease with which

they seem to be able to either bring down or infiltrate supposedly secure sites

should bring into question the wisdom of having so much personal information

stored in one location, undoubtedly attacked to the internet.