Discussions about the CPU

battleground usually focus on Intel and ARM, but MIPS is an exciting newcomer

to the mobile CPU market.

Founded in 1984 by researchers from

Stanford University, MIPS had some successful early years. Its high-speed yet

low-power instruction set was used Silicon Graphics for its workstations, with

the company later buying what was then known as MIPS Computer Systems

Incorporated, and rebranding it as MIPS Technologies in a deal valued at $499

million. The target of the deal was the technology behind the R2000 and R3000

processors. Launched to compete with Intel’s 386 and Motorola’s 68000, the

R2000 was the first readily available reduced instruction set computing (RISC)

processor beating ARM’s first available design by two years.

MIPS’s

proAptiv design includes some neat tricks to keep data flowing

AS a RISC chip, the same benefits of ARM’s

designs such as reduced transistor count compared to CISC and reduced power

draw for similar performance applied to MIPS processors, making them an obvious

choice for the burgeoning handheld computer market. In the early days of

Windows CE palmtops, MIPS and ARM would go head to head, but only one winner

emerged: ARM. When Microsoft moved from Windows CE to Windows Mobile and

Windows Phone, MIPS support was dropped in favor of a dual-architecture ARM

andx86 approach.

Having lost what would later be recognized

as the fight to be at the forefront of the Smartphone revolution, MIPS licked

its wounds and concentrated on other areas. Its high-performance, low-power

architecture found enough traction in networking and high-performance computing

(HPC) markets to keep the company afloat. Now MIPS is back and it intends to

remind ARM that, while it may have won the battle, the war isn’t yet over.

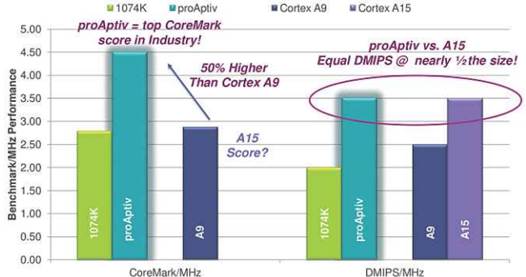

The

proAptiv IP scales up to six cores, each of which is claimed to be 50 per cent

faster than an ARM Cortex-A9

Software support

The first hints that MIPS was looking to

get back into the handheld market came in June 2009, when the company announced

that Google’s Android platform had been ported to the MIP instruction set

architecture. Later that year, MIPS would announce membership of the Open

Handset Alliance, confirming, if there was any doubt, that it was looking at

the mobile market afresh. Under new chief executive Sandeep Vij,

Android-related announcements came thick fast, including the launch of the

Ainol 7in ‘Ice Cream Sandwich’ tablet, the first such device to retail for

under $150. More recently, Karbonn Mobiles was the second company in the world

to announce an Android 4.1 ‘Jelly Bean’ device, based again on a MIPS

processor. As with ARM, MIPS doesn’t make chips, but sells designs to

third-party manufactures. Unlike a manufacturing company such as Intel, which

has to find the cash to produce enough processors to meet demand, MIPS and ARM

can sit back and watch the licensing fees come flooding in – leaving their

various partners holding most of the risk. It’s this risk that’s slowing the

adoption of MIPS over ARM in the mobile industry, with most companies still

opting for the tried-and-tested British option, but a design is coming that

promises to change all that: the MIPS proAptiv core.

Mips proaptiv

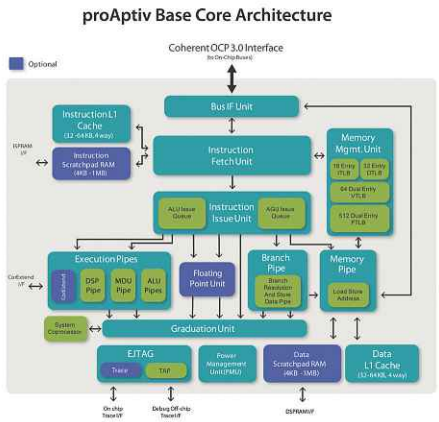

Designed for the performance market, the

MIPS proActiv ticks a lot of boxes: available in single, dual, quad or hex-core

flavors, the processor uses a fused triple- dispatch superscalar out-of-order

execution engine, and high-performance floating-point unit, all in a bundle

that takes up less space than the equivalent design from ARM while boasting

equivalent or greater performance.

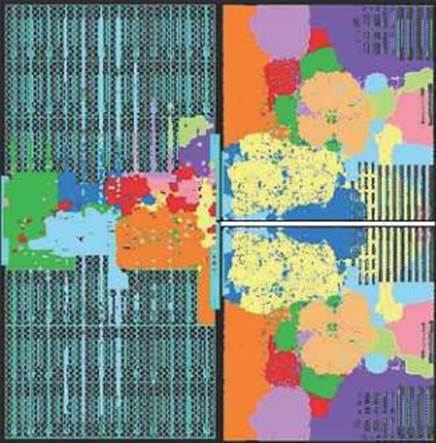

A

dial-core proAptiv design can fit 1 MB of L2 cache into the same space that an

ARM’s Cortex-A15 needs for the processors alone

Using details released at ARM Tech Con,

MIPS predicts that a dual-core proAptiv chip with 1MB of L2 cache will be just

over half the size of a dual-core Cortex-A15 chip, so you can pack four

proAptiv cores into same space. For devices where every millimetre counts but

high performance is demanded, that’s a powerful argument for a move to MIPS.

Cortex-A15 performance metrics are hard to

find, but are readily available for chips based on ARM’s Cortex-A9 design and

MIPS looks like an early winner. Using the CoreMark benchmark, the ProAptiv

design achieves a score of 4.5 per MHz, some 50 percent hiher than the

Cortex-A9 that’s at the heart of most modern smartphones and tablets.

Considering that the Cortex-A9 design is the basis for high-performance

processors, including Nvidia’s Tegra 3 and Samsung’s Exynos, that’s a pretty

impressive figure.

Just in case you thought MIPS might just be

bad-mouthing the competition, the company is quick to point out that the proApitv

design leaves its own last generation products in the dust too, with a boost of

around 60 per cent compared to its CoreMark per-megahertz results from the

previous MIPS 1074K series.

MIPS

claims that the proAptiv design easily bests the competition, but will OEMs be

convinced?

Under the bonnet

These performance gains come from a wealth

of improvements compared to MIPS’ earlier designs, including some clever tricks

such as the use of instruction bonding to make a single memory system. There’s

also an Enhanced Virtual Addressing [Eva] system for better address space

utilisation, and a sophisticated branch prediction engine that promises fewer

cache misses.

The floating point unit is also

particularly clever. Unlike previous designs, which ran the FPU at a slower

speed than the main processor, the proAptiv design runs the FPU at the same

speed as the CPU. As a result, latency is reduced and the throughput improved,

while the smart use of dedicated schedulers and increased parallelism means

that more instructions can whizz through the system than ever before.

A second-generation coherence manager also

boosts performance, boasting a design that drops latency from around 24 cycles

to 11 and offers around double the system bandwidth over the

previous-generation engine. There’s also a dedicated L2 cache controller within

the coherency manager itself; this required a separate component in previous

designs.

The family of chips envisioned by MIPS

covers a wide spectrum; mobile and tablet versions running between 1GHz and

1.5GHz will feature single, dual or quad-core designs and an integrated

digital-signal processor, while set-top box versions not encumbered by battery

like – will reach 2GHz.

The same architecture will also power

future network devices, with single to hex-core implementations running at

speeds between 1GHz and 2GHz.

The proAptiv design is joined by the

interAptiv and microAptiv families, each cheaper but less powerful than the

last. With the microAptiv, MIPS is even targeting traditional microcontroller

markets held by the likes of Atmel and NXP the latter, funnily enough are now

readily available, meaning that it’s to the company’s customers to make

products based on the chips.

MIPS vs INTEL vs ARM

While Intel and ARM have been fighting,

MIPS has been quietly working on the proAptiv design, and it’s now coming out

of left-field. Suddenly the two giants – one holding a near-monopoly in the

smartphone and tablet market, and the other holding a similar position in the

desktop, laptop and server markets – are fighting a war on three fronts, and

should MIPS’ claims for the benefits of proAptiv sway OEMs, both could lose

serious ground in an increasingly lucrative market.

The coming fight is something of a David vs

two Goliaths epic while Intel has more than 100,000memployees throughout the

world, and ARM has around 2,000, MIPS is a much smaller organization of around

160. Whether that will help MIPS with increased flexibility, or hinder it with

a lack of resources, in competing with two of the biggest names in the chip industry

remains to be seen.