We examine the changes that might herald a

new Intel - one that’s not as enthusiast-friendly as we’ve become accustomed to

Intel has ruled the roost in computing

silicon since the early eighties, and capitalising on its x86 architecture

(together with partners like Microsoft) it has built a massive technology

empire. Nothing lasts forever, though, and with an ever-changing technological

topology shifting beneath its very feet, is Intel planning to do something

drastic for the longer term viability of the company?

These

Intel Roadmaps suggest that Haswell will be the last of the desktop processors

to be available in a socket, but is that true?

A Changing World

Most people have grown up with Intel

powering the world’s computers. ‘Intel Inside’ has become an assumption most

people make upon seeing a system because, apart from some very odd times in the

past 30 or so years, Intel always made the best desktop PC processors. What’s

more, it has largely dominated the mobile computing space too, until recent

times and the growth of ARM in the tablet and smartphone markets.

That’s not to deride AMD’s attempts to

challenge it for desktop supremacy, and that company’s undoubted influence on

the technology we have now. The thing is, at no point did it ever look like

Intel would take the runners-up medal in the race to be the biggest chip maker

in desktop computers, and AMD has never managed to show it a clean pair of

heels.

What’s fascinating about Intel is that it

built a simple but effective chip selling business and, off the back of the

success of the IBM PC, rode it to billions of chip sales and many more billions

in yearly profits. Unfortunately, having all-but neutralized AMD, it then sat

back to enjoy a few decades of ‘business as usual’, and somewhat failed to

notice how the landscape of consumer computing was subtly changing.

LGA

2011 has a horribly complicated socket. Perhaps Intel isn’t being daft in

trying to do away with all these potential points of failure

Intel has had a few diversions away from

the venerable x86 format, most notably The Disaster That Shall Not Be Discussed

(aka Itanium) and a low power offering in the form of the Atom. The problem is,

the Itanium has become a technological funeral pyre on which HP is slowly being

roasted, while the Atom didn’t exactly set anyone’s world alight. It turns out,

though, while the Atom was wrong product, it moved the company in the right

direction - because the (then) unseen assassin that was ready to strike from

the shadows was the company formerly known as Advanced RISC Machines (now ARM

to its friends, and its enemies), and its amazing low power devices.

The launch of the Apple iPhone back in 2007

started a chain of events that Intel never anticipated, and propelled ARM from

being a company that historically came from Acorn and the BBC Micro to

challenge Intel’s domination of the world processor market.

“If it is true, then this is the most

radical change of direction that Intel has ever made, though that might also

reflect the seriousness with which the decline of the desktop market is viewed

internally”

It’s not that ARM itself makes all the

chips that go in phones, tablets, cameras, NAS boxes and Raspberry PI’s, it

actually licenses its tech to a variety of companies that make their own

flavours of its special sauce. It’s proving to be a very profitable recipe,

that’s for sure.

In contrast, it’s taken Intel five years to

enter the smartphone market. The distance between it and ARM was then put in

sharp relief when press releases with headlines like ‘Intel Cracks Smartphone

Apps Processor Market’ heralded it’s capturing of a record 0.2% share of that

market in 2012 (after delivering precisely 0% in 2011. ‘Scuffs’ is probably a

better word than ‘Cracks’ to describe its success in this sector so far. By its

own standards, its a long way from domination, and it has also failed to make

much of a dent on the tablet market either, which is again entirely dominated

by ARM-derived products.

With the momentum moving away from the

company, it’s not surprising that it’s making plans to wrestle back the

initative.

2013, And All Haswell

Roadmaps are a tasty source of information,

if you’re adept at reading between the press releases and filling in the

obvious omissions yourself. A fine example of the Intel’s approach to such

activities, is its Desktop Platform Roadmap, covering the period Q1 2012 to 1H

2013.

It covers the last of the Sandy Bridge

generation, and the continuation of the Ivy Bridge range we’re currently

enjoying, before priming us for the introduction - sometime between March and

June of next year - of it’s next step forward: ‘Haswell’. Eagled-eyed readers

of the map quickly noticed that, while Ivy Bridge covers LGA 1155 and Sandy

Bridge-E takes the LGA 2011 high ground, Haswell is to be given a whole new

Socket (1150). Quite why it needs to dispense with five pins isn’t obvious, but

on the surface it could be said to adhere to Intel’s modus opperandi of

changing sockets on a regular basis to keep motherboard manufacturers in

business.

This

is the machine you need to either install or remove a BGA packaged CPU, which

most people don’t own

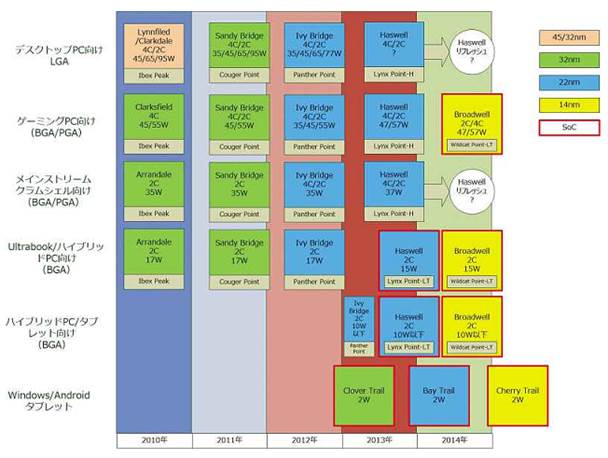

This raised few eyebrows, but more

speculation spawned from the release of a Japanese chart showing that Haswell

itself will be followed by a new chip ‘Broadwell’ in 2014 (reportedly on an

amazing new 14nm fabrication). What socket will Broadwell be on? Well the chart

says ‘SoC’, which means ‘System on a chip’, which infers that this CPU won’t be

on a socket because it carries many of the support chips with it and can be

surface-mounted to a motherboard. The technical term for this is a ball grid

array (BGA), and that’s the same technology that Intel has used with the Atom,

which isn’t replaceable by a user.

If true, then Haswell’s legacy could be to

represent the very last socketed desktop processor produced by Intel. Beyond

that line, you could well be buying an entirely new motherboard in order to upgrade

the processing power of a system.

The general plan with Broadwell is that the

chip will carry the CPU, GPU and integrated memory controller (as with current

designs) and that it will be coupled with a Wildcat Point input/output

controller. That chip will be created with various power envelopes for mobile

and desktop use, and it will dictate what the Broadwell chip is capable of

doing in terms of clock speed and turbo mode.

If this really is the intention then it

represents the commoditisation of the PC into an appliance, and potentially the

end of enthusiast -built and tweaked systems entirely.