For a keyboard jockey who recently started

working from home in the wettest winter since the biblical Flood, the results

can be disheartening. On one day, I took a mere 2,678 steps: a total distance

of only 1.3 miles. There are people in comas getting more exercise than that.

Astonishingly, however, according to one of Fitbit’s “premium reports” - for

which it charges another $67 per year - I’m doing 11% more exercise than the

median for all people in the UK, at an average of 7,463 steps a day. I’m not

sure whether that makes me feel better about myself, or depressed at the state

of the nation’s health.

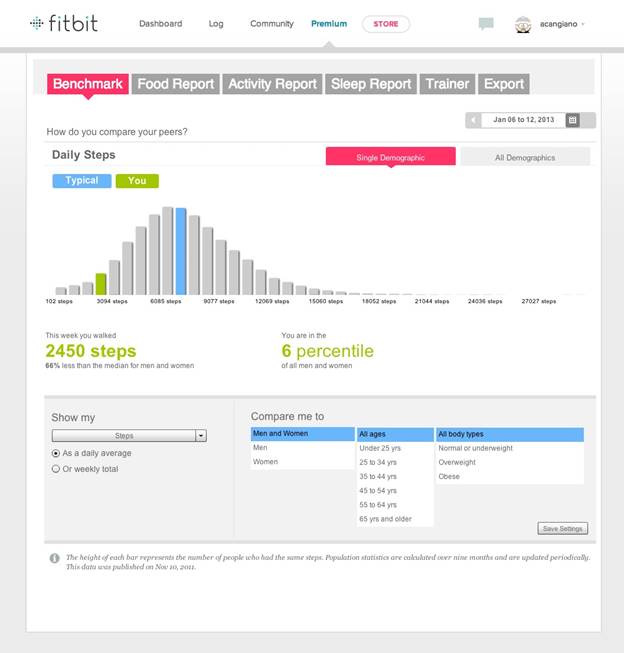

Benchmark

compares the number of steps performed

against other users in similar demographics

Fitbit’s hopeless if you decide to hop on

your bike to do some exercise: it’s a pedometer, not a GPS device, so it will

probably think you’re tucked up on the sofa watching Breaking Bad when you’re

actually breaking your back down country lanes. Here, apps that take advantage

of the GPS chips in smartphones, such as the free for iOS and Android, come

into play.

On

the Explore Page on the Strava Cycling App,

letter markers save rides that previous cyclists have ridden.

Strava places much greater emphasis on

competition than Fitbit: not only handing out badges for clocking up so many

miles or climbs, but pitting you against your friends and the entire Strava

community. Strava automatically breaks down your rides into different segments,

and shows you how pitifully slow you are compared to those with Chris Hoy’s helmet

and a bike that weighs less than a Mars Bar. On one 2.5km stretch near my home

- the London Lollop - I’m currently sitting in 314th position, with a time

that’s more than twice the leader’s.

Strava has been criticised for encouraging

cyclists to take unnecessary risks to climb leaderboards or beat personal

bests, and it’s easy to see why. It’s also clever at parting members from their

cash as well as their senses: if you completed February’s challenge of 130km in

a single ride, you “unlocked the ability to purchase a limited edition Gran

Fondo Jersey made by Castelli for $109”. Yet, if you can avoid the temptation

to risk life and limb to beat Colin from Hemel Hempstead, or to buy an

expensive jersey, reviewing the detailed telemetry from your rides can be

hugely satisfying.

Complete

the Challenge and you will unlock the ability to

purchase a limited edition Gran Fondo Jersey made by Castelli for $109.

Sleep

After a hard day’s cycling, you’re going to

need a good kip. As I mentioned above, Fitbit not only measures how active you

are during the day, it also measures how inactive you are at night. Tap

repeatedly on the wristband for a second or two, and the device is put into

Sleep mode, designed to measure if you’re getting your eight hours.

Fitbit considers you’re asleep if it

doesn’t detect any motion from the band strapped to your wrist - a methodology

that isn’t without its flaws, in my experience. I know for a fact that I’ve

been awake for periods when Fitbit claims I was clocking up shuteye, presumably

because I wasn’t thrashing around like a demented salmon. However, Fitbit is

excellent at detecting periods of restlessness during the night, and after a

week or so of usage, patterns started to become clear: I’d often start to

wriggle around at 2am, and then again at around 5am.

Other trends emerged. Perhaps not

surprisingly, I slept better when my partner and young children weren’t in the

house. Contrary to received medical wisdom, I also slept better - if not for

longer - after drinking alcohol, showing far fewer periods of restlessness.

This is where collecting all this data begins to pay off, as you can match up

information from different sets of data to identify trends.