The technical background for Silverlight's downloader API is the XMLHttpRequest JavaScript object, which

fuels everything Ajax. The Silverlight API does not copy the

XMLHttpRequest API, but provides its own interfaces.

You can trigger the API from both XAML code-behind and HTML code-behind

JavaScript code, but generally you will want to start from XAML.

When downloading content from within Silverlight, you usually have

to follow these steps:

Initialize the downloader object by using the plug-in's

createObject() method.

Add event listeners to the object to react to important

events.

Configure the downloader object by providing information about

the resource to download (HTTP verb, URL).

Handle any occurring events.

We will go through these step by step. But first we need some XAML

backing so that we can wire up the code. Example 1 shows

a suggestion.

Example 1. Downloading content, the XAML file (Download.xaml)

<Canvas xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/client/2007"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml"

Loaded="loadFile">

<Rectangle Width="300" Height="150" Stroke="Orange" StrokeThickness="15" />

<TextBlock x:Name="DownloadText" FontSize="52"

Canvas.Left="25" Canvas.Top="35" Foreground="Black"

Text="loading ..."/>

</Canvas>

|

Once the XAML has been loaded (via the Loaded event in

the <Canvas> element), we start working on the

download. Step 1 is to create the downloader object. For that, we first

need to access the plug-in and

then call the method:

function loadFile(sender, eventArgs) {

var plugin = sender.getHost();

var d = plugin.createObject('downloader'); Step 2 is to set up event listeners. Three events are

available:

- Completed

-

The download has completed.

- DownloadFailed

-

The download failed—for instance, because the URL does not exist, or there was

an internal server error, or security restrictions prevented the

download.

- DownloadProgressChanged

-

Another chunk of data has been downloaded from the server; there may be more to come.

For this example, the Completed event is what we

want:

d.addEventListener('completed', showText);

Step 3 is to configure the downloader object, which we do

using the open() method (this does not actually open

the connection, but just configures the object). Provide the HTTP verb

(usually 'GET'), and the URI to request.

d.open('GET', 'Download.txt'); Step 4 is easy. The

send() method

does exactly what it says—it sends the HTTP request:

d.send();

Finally, in step 5, you need to implement the event handlers; in our

case, there's just one. The first argument for that event handler (we call

it

sender, as always) is conveniently the downloader object.

It provides you with two options to access the data returned from the

server:

- responseText

-

This property contains the response as a string.

- getResponseText(id)

-

This method returns one specific part of a response. If you download a ZIP

file, you can provide the filename inside the archive that you

want.

In this example, we use the former option and output the

text:

function showText(sender, eventArgs) {

var textBlock = sender.findName('DownloadText');

textBlock.text = sender.responseText;

}

Now all you need is a file called Download.txt (see the open()

method call for the filename) residing in the same directory as your

application, and you can download the file. After a (very) short while,

you will see the content in the <TextBlock> element.

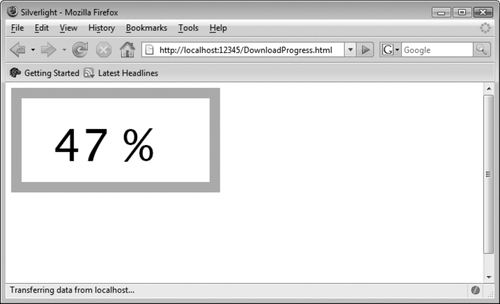

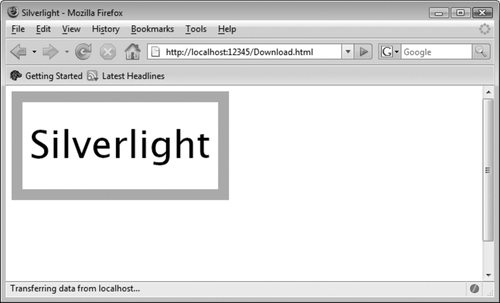

Example 2 contains the complete XAML code-behind

JavaScript code, and Figure 1 shows the output. If you

are using a tracing tool such as Firebug (see Figure 2), you will see that the text file is actually

downloaded.

Example 2. Downloading content, the JavaScript file (Download.js)

function loadFile(sender, eventArgs) {

var plugin = sender.getHost();

var d = plugin.createObject('downloader');

d.addEventListener('completed', showText);

d.open('GET', 'Download.txt');

d.send();

}

function showText(sender, eventArgs) {

var textBlock = sender.findName('DownloadText');

textBlock.text = sender.responseText;

}

|

|

Downloading works only when you're using the HTTP protocol. You

cannot use the file: protocol (which means that you have to

run these examples using a web server, even if it is a local one). You

also have to adhere to the same-origin policy of

the browser security system. The URL you are requesting

must reside on the same domain, use the same port, and use the same

protocol.

|

|

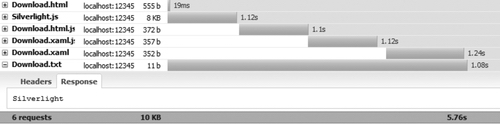

It's a good idea to provide the user with information on how long

downloading big files will take. The DownloadProgressChanged

event is an excellent choice to implement this. We start off again with a

simple XAML file (see Example 3) that both starts

JavaScript code once the canvas has been loaded and includes a text block

that will hold the progress information.

Example 3. Displaying the download progress, the XAML file (DownloadProgress.xaml)

<Canvas xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/client/2007"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml"

Loaded="loadFile">

<Rectangle Width="300" Height="150" Stroke="Orange" StrokeThickness="15" />

<TextBlock x:Name="ProgressMeter" FontSize="64"

Canvas.Left="60" Canvas.Top="35" Foreground="Black"

Text="0 %"/>

</Canvas>

|

The best way to simulate a big file is to write a script that does

not return that much data, but takes some time to run. The ASP.NET code

from Example 4 sends only a bit more than 1,000 bytes,

but takes a break every few dozen bytes. Therefore, the script is

continuously sending data, but taking a few seconds to finish.

Example 11-4. Displaying the download progress, the ASP.NET file simulating a

big or slow download (DownloadProgress.aspx)

<%@ Page Language="C#" %>

<script runat="server">

void Page_Load() {

Response.Clear();

Response.BufferOutput = false;

Response.AddHeader("Content-Length", "1003");

for (int i = 0; i < 17; i++)

{

Response.Write(

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA");

System.Threading.Thread.Sleep(500);

}

Response.End();

}

</script>

|

|

It is very important that the script, in whatever language it is

written, does not use output buffering and also sends the correct

Content-Length HTTP header. Otherwise, Silverlight cannot know how many bytes the

server will send in its response, and thus cannot determine the

percentage of data that has already been sent.

|

|

Now we're ready for the JavaScript part. The beginning is easy:

create a downloader object and send an HTTP request. Only this time, we

are listening to the DownloadProgressChanged event:

function loadFile(sender, eventArgs) {

var plugin = sender.getHost();

var d = plugin.createObject('downloader');

d.addEventListener('DownloadProgressChanged', showProgress);

d.open('GET', 'DownloadProgress.aspx');

d.send();

}

The downloader object exposes a property called downloadProgress, which returns a value

between 0 and 1, which is a percentage of how much data has already been

transferred. When it is multiplied by 100 (and rounded), you get a nice

percentage value that can be displayed in the

element. Without further ado, Example 5 contains the complete

JavaScript code.

Example 11-5. Displaying the download progress, the JavaScript file (DownloadProgress.js)

function loadFile(sender, eventArgs) {

var plugin = sender.getHost();

var d = plugin.createObject('downloader');

d.addEventListener('DownloadProgressChanged', showProgress);

d.open('GET', 'DownloadProgress.aspx');

d.send();

}

function showProgress(sender, eventArgs) {

var progress = sender.downloadProgress;

var textBlock = sender.findName('ProgressMeter');

textBlock.text = Math.round(100 * progress) + ' %';

}

|

Figure 3 shows the result—the file is loading,

and loading, and loading.