With steam coming to Linux which way to turn

for gaming graphics joy?

Perhaps the most subjective component in

any hardware discussion is the one responsible for generating the graphics. This

is because the best choice for you will depend on how important graphics are in

your system. If you use the command line or a simple window manager, for

example, and expensive, powerful card will be a waste of money. This is because

it’s in the realm of 3D graphics that most graphical processing units (GPUs)

differ, and they often differ dramatically.

GPUs

Although 3D rendering capabilities used to

be important solely for running 3D games, the mathematical powerhouses

contained within a GPU are now used for lots of other tasks, such as HD video

encoding, the decoding, mathematical processing, the playback of DRM-protected

content, and those wobbly windows and drop shadows everyone seems to like on

their Ubintu desktops.

A better hardware specification not only

means that games run at a higher resolution, at a better quality and with a

faster frame rate – all of which adds to your overall enjoyment – it now means

you also get a better desktop experience.

Processing

Like CPUs, the development of GPUs never

seems to reach a plateau. Their power seems to double every 18 months, and this

is both a good and a bad thing. The good is that last year’s models usually

cost half as much as they did when they were released. The bad is that your

card is almost always out of date, even when you buy the most recent model. For

those reasons, and because most Linux gamers won’t want cutting edge gaming

technology when there are no cutting-edge titles to use it on (unless you

dual-boot to Windows), we’re going to focus our hardware on value, performance,

hardware support and compatibility.

At the value end of the market, we’re going

to look at models slightly off the cutting edge, including a couple of cheap

options and a few that are more expensive. For performance, we’ve run each

device against version 3.0 of the Unigine benchmark. This is an arduous test of

3D prowess, churning out millions of polygons complete with ambient occlusion,

dynamic global illumination, volumetric cumulonimbus clouds and light

scattering. It looks better than any Linux-native game, and it tests both for

hardware capabilities and the quality of the drives. As the Unigine engine is

used by a couple of high profile games, including Oil Rush, its results should

give a good indication of how well a GPU might perform with any modern games

that appear.

However, we also wanted to test our

hardware on games that you might want to play now. We tested the latest version

of Alien Arena, for example, as well as commercial india titles such as World

of Goo. More importantly, we also tested the kit with some games from Steam

running on Wine. Steam is games portal for Windows, and it has become the best

way of buying and installing new games for that operating system. There’s some

very strong evidence that Stream will be coming to Linux before the end of

2012. If that happens, its Wine performance should give us some indication of

how certain Steam titles will run on Linux.

Hardware

We tested five different GPUs. The first

two are integrated, which means they’re part of the CPU package rather than

being discrete cards that you slot into your motherboard. These CPU and

graphics packages were the norm in the old 2D days, but since 3D gaming

demanded more powerful GPUs integrated on die.

Speed

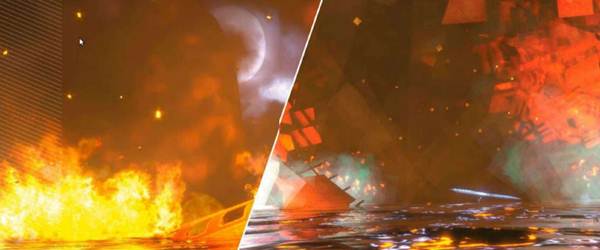

isn’t the only consideration. Rendering quality is also important. The Radeon HD6850

(right) has a problem with textures in Bioshock. The Nvidia GTX570 (left)

doesn’t

We started with Intel’s HD 3000 on the

i5-2500K CPU, and because Intel takes Linux driver development seriously, we

expected great results from a single package. The other integrated part we

tested has got a much better specification on paper; and that’s the one that

comes with AMD’s A8-3850 APU package (aka AMD Fusion). This is the rumoured

core of a PlaySation 4, and although the GPU on our model is likely to be less powerful

than Sony’s eventual successor, it will still be possible to combine its

computational power with another external Radeon card using the hybrid

CrossFire option enabled from the BIOS. It’s listed as an AMD Radeon HD 6550D,

and we used it with 512MB of assigned VRAM. The remainder of the cards we

looked at were discrete, and connect to a spare PCIe slot on the motherboard.

With this method, you need to make sure you’ve got two spare slots, because a

graphics card will often occupy an adjacent slot for extra cooling, and that

your power supply is capable of providing enough raw energy. We used a 600w

supply, with two separate 12v rails for powering graphics hardware. Our cards

needed additional power: a single additional six-pin connector, or two connectors

for the most power-hungry – the Nvidia card. The models we looked at were the

cheap AMD Radeon HD 6670 (which is one of the cards designed to work with the

A8-3850 APU), the more powerful AMD Radeon HD6850 and the Nvidia GTX570, and we

tested with both open source and proprietary drivers.

The

GPUs on test

For every device other than Intel, our test

system was the AMD A8-3850 2.9GHz CPU, with 4GB of RAM running a standard

64-bit installation of Ubuntu 12.04. We used 2D Unity to avoid any conflict

with the graphics acceleration.

·

Intel Sandy Bridge i5-2500K: $217.5

·

AMD Radeon HD 6550D: $118.5 (with A8-3850 CPU)

·

AMD Radeon HD 6670 1GB: $75

·

AMD Radeon HD6850 1GB: $135

·

Nvidia GTX570 1.25GB: $270