Thingternet (n) 1. A Portmanteau of

“thing” + “internet”. 2. A network of objects connected to other objects, via

the internet. 3. The future.

On any given day the internet will deliver

around 300 billion emails, help YouTubers upload the equivalent of 35,000

films, and support the digital lives of 2.27 billion people. The internet is a

rather busy place. But busy as it is, we’re still at the very beginning of the

internet’s big bang. How so? Because all of these examples, at some stage,

involve people – people typing messages, people uploading videos, people

stalking fellow humans on social networks. This kind of human-powered

internetery is soon going to seem rather small and frivolous. In the internet

of the near future, most traffic will take the form of a perpetual, global

chatter from sensor equipped machines and objects. The physical world will go

online and unlike your Facebook friends, its sole aim will be to lubricate

life’s annoying frictions and to make your existence easier. Welcome to the

thingternet.

Thingternet

(n) 1. A Portmanteau of “thing” + “Internet”.

Here’s The Thing

Futuristic as it sounds, the idea of an ‘internet

of things’ is far from new. Invent a Holic Nikola Tesla predicted it in the

1920s, and in the 1990s influential Xerox scientist Mark Weiser spoke of the

rise of ‘ubiquitous computing’. “Ubiquitous computing is roughly the opposite

of virtual reality,” he explained. “While virtual reality puts people inside a

computer-generated world, ubiquitous computing forces the computer to live out

here in the real world with people.”

That scenario was slightly beyond the 56k

modems of the time but luckily for us, two recent tech advances have given the

thingternet a crucial springboard. In February 2010 we ran out of fresh IP

addresses, but a new protocol called IPv6 arrived with longer URLs. Creating more

than 340 Undecillion (that’s 340 trillion trillion trillion) possible

addresses. It’s enough to give every atom on the surface of the Earth a unique

address on the internet. Try cybersquatting on all of them. Equally important

is the arrival of cheap, smart sensors and affordable, long-life chips such as

ARM’s Flycatcher. Consider the RAD750 PowerPC microprocessor in the Curiosity

Mars rover. Your phone is ten times as powerful, but Curiosity’s brain is built

to deal with high-energy cosmic rays and anything a 15-year space mission could

throw at it running sensors and chips on Earth is a cinch in comparison. But it

raises one question – the components may be cheap and long-lived, but how will

we power the millions that a thingternet will require?

Power Rangers

That little poser was answered in May 2012

by researchers at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology. They

announced the development of a simple, low-cost Nano generator that can convert

vibrational and mechanical forces such as wind and wave movement into electric

current. Zhong Lin Wang, lead scientist at the Georgia Institute of Technology,

which is also developing Nano generators, believes they’ll be a revolutionary

fuel for the thingternet. “[They] are poised to change lives,” he says. “Their

potential is only limited by one’s imagination.” Not that the tech world has

been short on imagination when it comes to connecting ‘things’ to the internet.

Nike+ has been using web-connected sensors to get our trainers hooked up since

2006. Withings’ family of smart health gizmos, which first appeared in 2009,

all use simple sensors to connect to devices such as smartphones and tablets. And

this year, Berg’s Little Printer gave us a smooth implementation of the

thingternet, in the form of a web-connected printer that feasts on feeds to

produce snack-sized, thermal-printed updates.

That

little poser was answered in May 2012 by researchers at the Korea Advanced

Institute of Science and Technology.

Year Of The Thingternet

A future issue of Stuff-May well mark 2012

as the moment the Thingternet sparked into life. There are products everywhere:

Evernote’s Smart Book /Thingternet is a Moleskine notebook that works with the

app to scan text recognized pages straight to your Evernote account, while the

Insteon Light Bulb ($30,smarthome.com) networks directly to your smartphone.

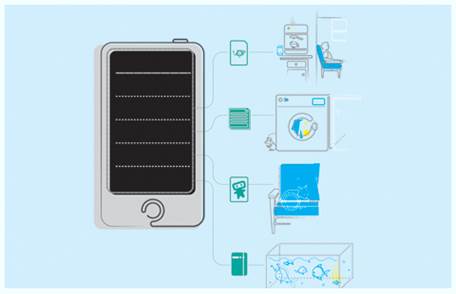

New systems such as Mavia, Green Goose or Belkin’s WeMo home automation (see

boxes) show how simply we’ll be able to communicate and interact with almost

every object.

Belkin’s

WeMo home automation shows how simply we’ll be able to communicate and interact

with almost every object.

This slickly packaged tech isn’t the only

way to bring the thingternet into your life. Kickstarter projects such as Twine

(from US$100, supermechanical.com/twine) are sensor packed boxes that connect

your appliances to a cloud service and have you define rules for them for

example, ‘send me a tweet when the laundry’s done.’ For even more DIY types,

there’s the Arduino microcontroller or Electric Imp (from US$25,

electricimp.com), an SD card-shaped, Wi-Fi enabled chip for easy Thingtegration.