Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, 2.4GHz, Miracast and more: Darien

Graham-Smith explains each of today's numerous wireless standards

A similar concept is the 802.11ad protocol,

branded “WiGig” after the Wireless Gigabit Alliance that developed it (now

incorporated into the Wi-Fi Alliance). WiGig can use low-frequency

communications to talk to a device that’s 10m away on the other side of a wall,

or automatically switch up to 60GHz to communicate with a device sitting right

next to the transceiver at up to 7Gbits/sec. The technology hasn’t caught on in

the mainstream, but the USB Implementers Forum is working on a new approach to

wireless USB that will function over WiGig as well as Wi-Fi networks, so the

technology could yet have its day.

WiGig

can use low-frequency communications to talk to a device that’s 10m away

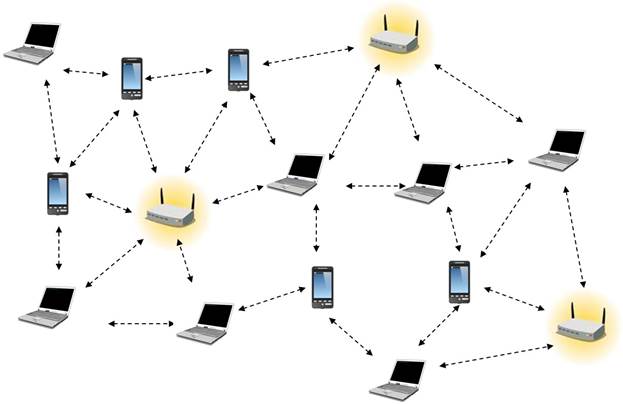

A more advanced wireless interconnect is

Wi-Fi Direct, a standard that lets any number of Wi-Fi-equipped devices

exchange files and information directly, rather than having to go through a

router. Only one device needs to support Wi-Fi Direct - the others will simply

see it as a regular access point - but range and bandwidth will depend on the

hardware, and on which Wi-Fi standard is being used (we’ll get into these

issues later). Many smartphones and tablets can act as hosts, as can the Xbox

One; you can already buy mice, loudspeakers and printers that support Wi-Fi

Direct connections.

Wireless display

The Miracast standard lets you transmit

video wirelessly to a TV or monitor by sending an H.264-compressed stream over

an 802.11n Wi-Fi Direct link. Support is already built into a number of Android

devices, and recent Ultrabooks that support Intel’s own WiDi wireless-display

technology can talk directly to Miracast-compatible displays. OS support is

built into Windows 8.1.

The

Miracast button displays the EZMirror screen

Few TVs are directly compatible with

Miracast, but you can buy a receiver for around £60 that plugs into your TV via

an HDMI cable. The catch is latency: it takes time for the transmitting device

to encode the video stream, and more time for the receiver to decode it again.

Officially, Intel’s latest drivers cut this

down to 60ms, but we’ve seen external displays lag behind the built-in one by

up to a second. That’s fine for presentations and movies, but a disaster for

games.

Apple devices don’t currently support

Miracast, but the proprietary AirPlay system does a similar job, letting you

use a television to mirror the screen of a Mac or iOS device. A selection of

receivers is available, with prices starting at around £30; you can also use an

Apple TV appliance.

Ad hoc connections

The

first and the most important design decision that

we made was to adopt the paradigm of ad hoc communication

Some wireless technologies aren’t intended

for persistent connections, but for ad hoc data sharing. The most extreme

example of this is the radio-frequency identification (RFID) tag - a tiny

transmitter that shares a single piece of programmed information with any

receiver that comes near to it. RFID technology is commonly used for access

management, so an automated door might open only when it detects an RFID tag

with a valid identity, or a reader on a London bus might use the RFID chip

embedded in your Oyster card to log your journey. Contactless payment systems

work in the same way, and modern UK passports include an embedded RFID tag

detailing the holder’s personal information, since this is quicker to read

electronically and harder to falsify than a printed page.