We put Apple's latest storage option

through the paces to see if it's a good alternative to an SSD, and to look at

how the technology can improve your current Mac

When Apple updated the iMac and Mac mini in

late 2012, it introduced a new storage option called Fusion Drive. Despite the

name, it’s actually two drives working in a special arrangement. It pairs 128GB

of flash storage with either a 1TB or 3TB hard drive. Apple bills it as

providing the high capacity of a hard drive with the performance of flash

storage, in a way that has no impact on how you work and store things.

Pure SSD configurations remain an option on

some Macs, but they’re still costly for their capacities. Replacing a Mac

mini’s 1TB hard drive with a 256GB SSD costs $300, and a 768GB SSD on the

27-inch iMac is an eye-watering $900. Hence Apple’s attempt to find a

compromise between speed and capacity. Fusion Drives cost $250 and $400 for the

1TB and 3TB versions, respectively, though the latter is only available on the

27-inch iMac. In fact, Apple sells Fusion Drive short by listing only the hard

drive component’s capacity and omitting that of the SSD.

Mac

mini’s 1TB hard drive

In terms of hardware, all that’s added is a

128GB SSD. A substantial amount of what you’re paying covers the fitting of the

SSD, and the configuration of the two drives to work together. There’s no setup

process on your part.

The two drives that make up a Fusion Drive

don’t operate like a striped RAID array to spread the load between them. Nor do

they work like hybrid drives, available on PCs for several years, despite their

similar makeup. A hybrid drive’s flash portion acts as a cache, but that’s all

it is: a cache. A copy of everything is on the hard drive.

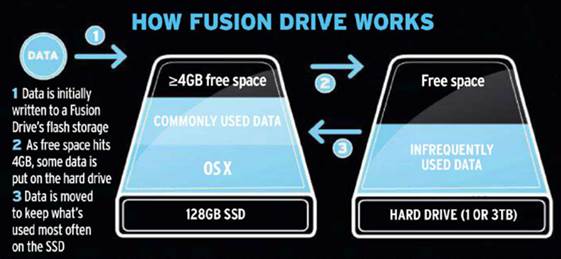

How does fusion drive work?

A Fusion Drive’s components appear as a

single volume in the Finder, with their capacities merged. No adjustment needs

to be made to how you work, as decisions about which of the two components is

used to store a given piece of information are made for you. Neither of the

drives holds a complete copy of everything.

When something needs to be stored, it’s

always first written to the flash storage. As long as plenty of free flash

storage is available, OS X doesn’t touch the hard drive, and the Mac will

operate solely from its flash storage.

Behind the scenes, OS X silently monitors

how your Mac is used. When free flash storage dwindles to only 4GB, OS X’s

long-term observations are used to decide what you’re least likely to need from

day to day, and it moves some of it to the hard drive. This keeps plenty of

flash storage available so that high performance is maintained.

Relegation to the hard drive isn’t one-way

or irreversible. OS X continues to monitor your activity, and if it discerns

you’re using something enough to warrant moving it back to the faster storage,

it will do so. Something else will end up relegated to the slower drive

instead. The operating system stays on the SSD, but pre-installed apps such as

iMovie and GarageBand don’t enjoy this privilege.

How

fusion drive works

Very large files, such as videos or an

iPhoto library aren’t treated as monolithic. That would be inefficient, so

Fusion Drive doesn’t have to shift the whole of a file. A developer, Patrick

Stein, has published blog posts examining the working of Apple’s technology. He

discovered Fusion Drive works at a lower level, instead moving the blocks that

make up files, and only some of them. Stein discovered if he read the first

megabyte of a large file enough to warrant storing it on the flash storage,

only that portion of the file was moved. The rest remained on the hard drive.

The effect of splitting data between two

drives is that both need to be connected to a Mac (which must be running OS X

10.8.2 or later) in order to read it. Under any circumstances, it’s wise to

keep an up-to-date backup of your Mac’s contents. OS X’s Time Machine feature

will back up a Fusion Drive just the same as it would a hard drive, and it’s a

good idea to use it because the contents are more susceptible to loss due to

the increased risk that either of the two pieces of hardware fails.

In our testing of two 21.5-inch iMacs – one

with a hard drive and the other with a Fusion Drive – OS X’s System Information

app revealed that the hard drives in both had the same model number and

rotational speed. The smaller iMac uses a 2.5-inch, 5400rpm drive. However,

Apple has stuck with 3.5-inch, 7200rpm drives in the 27-inch iMac, which are

capable of faster transfer rates. However, they fall far short of flash

storage’s capabilities, our benchmarks on the next page show the speeds reached

by a hard drive and a Fusion Drive in two 21.5-inch iMacs. The gap in their

performance is really quite significant.

Fusion Drive and boot camp

Since Fusion Drive depends on software

technology build into OS X, Windows doesn’t support it. This doesn’t mean

Windows can’t be installed on a Mac with A Fusion Drive, but Boot Camp

Assistant will only create a partition on the hard drive. However, there had

been an issue with installing on a 3TB drive, whether that’s a Fusion Drive or

a garden-variety hard drive. Apple seems to have come up with a solution with

an OS X update.

For those not willing or able to upgrade to

OS X 10.8.3, there is a workaround form the maker of WinClone, an app that

backs up Boot Camp partitions from within OS X. on the company’s blog, they

detail the reason for the issue and how to overcome it.

Some commenters on the blog entry report

stumbling at the final step, and even if it works for you, there’s a side

effect that might discourage you from trying of your Fusion Drive into three

partitions. OS X continues to see the first one as part of the Fusion Drive,

Windows can be installed on the second one, and the last 1TB of the drive

becomes a separate volume. It’s usable, but OS X no longer sees it as part of

the Fusion Drive, so it loses the ability to include that capacity in its

shifting around of data.

Make your own fusion drive

Adding a Fusion drive to a Thunderbolt

Mac isn’t cheap, but it’s less costly than replacing your existing Mac

Make

your own fusion drive

Among Patrick Stein’s posts about Fusion

Drive, he published instructions on how to use the command-line version of Disk

Utility to create your own Fusion Drive from any two drives connected to a Mac.

The Mac must support Mountain Lion, which is needed for Fusion Drive support.

Specifically, it requires the installer for OS X 10.8.2 from the Mac App Store.

There’s little reason to create your own

Fusion Drive unless one of the drives is capable of very fast transfer rates

though. That depends not just on the drive but also its connection to the Mac.

To get a real benefit requires, among other things, a Mac with Thunderbolt, a

Mac Pro with an SSD, or a willingness to make major internal changes to other

models.

For instance, on a MacBook Pro, you’ll need

to install a kit such as OWC’s Data Doubler ($45), which converts the bay

normally occupied by the SuperDrive to hold a 2.5-inch drive instead. The hard

drive needs to be moved there, since that bay typically uses a slower

connection that would impede an SSD’s performance. Even then, MacBook Pros

introduced prior to 2011 use a SATA-II connection, which impedes the transfer

rate of modern, SATA-III SSDs.

Apple doesn’t intent you to set up your own

Fusion Drive. The graphical version of Disk Utility doesn’t provide the

capability, but the command-line version accessed in Terminal does. On the next

page we’ll show you just what you need to roll your own Fusion Drive.

However, you won’t get all the benefits of

an Apple-provided Fusion Drive. TRIM is technology that prevents degradation in

an SSD’s performance over time as it’s repeatedly overwritten. It’s normally

enabled only for flash storage provided by Apple, but TRIM Enabler turns it on

for other drives. We installed TRIM Enabler on our Mac’s homemade Fusion Drive

and encountered no issues. However, doing so means you will be running OS X

with low-level modifications that take you further away from configurations

that are tested and approved by Apple.