The alternative software foundation that

SATA Express PCI-E devices will support is NVMe (Non-Volatile Memory Express),

which was built from the ground up to support SSDs. NVMe can handle up to

64,000 queues with 64,000 simultaneous commands each. NVMe was first proposed

in 2011, but SATA Express is the first time the technology has been implemented

and available (at least as engineering samples). As such, support for it is

significantly more limited than with AHCI.

IDT,

LSI, and Intel are members of the NVMe working group,

but more companies are sure to hop on board as the standard progresses

NVMe isn’t compatible with SATA software,

but you can visit nvmexpress page to access drivers for Windows, Linux, and

other operating systems. The LSI SandForce SF3700 controller family, which came

out late last year, supports NVMe-based devices, but none were available to

consumers for purchase at press time. At CES 2014, a Kingston HyperX prototype

with this controller (expected to support NVMe via post-launch firmware update)

can use four PCI-E 2.0 lanes to achieve up to 1,800MBps sequential read/write

speeds and 150K/81K random IOPS. NVMe-based components are slated to appear in

the second half of 2014.

SATA 3.2 Miscellanea

Typically, protocol revisions include a

number of improvements and changes, and SATA 3.2 is no exception. In addition

to SATA Express, the updated protocol also brings with it support for

microSSDs, or single-chip SATA SSDs that are ideally suited to embedded storage

applications. The Universal Storage Module, which was a part of the SATA 3.1

revision, gets a form factor revision, which shrinks the module’s thickness

from 14.5mm to 9mm, called USM Slim. This update is targeted at improving the

removable and expandable storage options for gadgets.

To bolster the protocol’s power efficiency,

SATA 3.2 includes the new DevSleep specification, which lets the storage device

conserve energy by entering a very low power state. This feature is designed to

improve battery life in Ultrabooks, as the new protocol’s Transitional Energy

Reporting feature, which provides the SATA host with granular data about the

storage device and its energy consumption to improve the efficiency of switching

between power management modes.

Innodisk

Releases World's First Industrial-Embedded SATA µSSD

With SSHDs (that is, hard drives with

integrated flash storage designed for caching) growing in popularity, SATA 3.2

contains a tweak that lets the host queue commands for the reading and writing

of log data, which improves performance of these types of storage devices.

Finally, those with a RAID array will

appreciate the new Rebuild Assist feature, which lets the SATA host identify

the corrupted data on a failed drive in the RAID array so that it can more

quickly rebuild that data on a replacement device.

When Can I Get SATA Express?

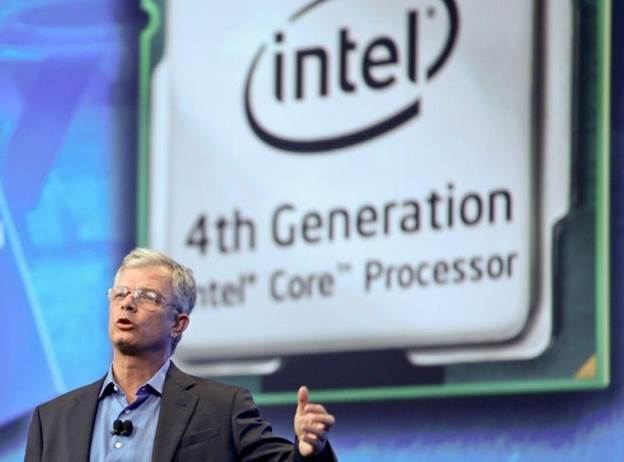

As we went to press, SATA Express was

nowhere to be found on Intel’s or AMD’s chipset roadmaps. That doesn’t mean

that the protocol won’t make the chipset varsity team eventually; it just won’t

be happening in the immediate future, namely in Intel’s Haswell-E revamp

scheduled to land later this year.

The

next generation Intel Haswell-E series

We don’t have a specific time frame for

SATA Express, but there are a lot of stars that have to align first.

Motherboard makers like ASUS and GIGABYTE have to begin selling retail boards

that support the standard; SATA Express controllers have to become available,

likely starting with LSI Sandforce, which may be holding out until NVMe

read/write performance (and, likely, OS-level driver support for NVMe) is good

enough to be a compelling alternative to AHCI-based devices; and finally, major

SSD manufacturers need to put those controllers to use by making SATA Express

PCI-E SSDs available for purchase. Arguably, all of these could happen in a

relatively short amount of time, or it could take significantly longer than

anyone expects. Our money’s on sooner rather than later.