If you still have the negatives of your old

photos, consider digitising these rather than any prints you may have had made

from them. Negatives contain more detail and are sharper than most prints, and

you’ll cut out any colour shifts and fading that have been introduced to prints

by years of exposure to the environment. Photographic negatives are also likely

to have been kept safely tucked away in their envelopes, so they’re less likely

to have been scratched, smudged or creased through handling.

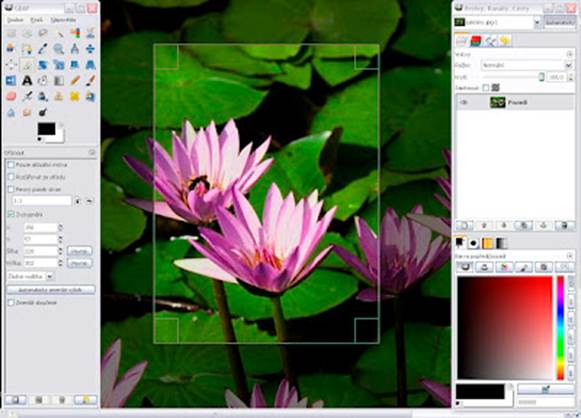

Paint.NET

To scan negatives, however, you’ll need a

scanner that can handle transparencies – something that’s beyond the abilities

of most all-in-one devices. For one thing, a negative scanner must have a light

integrated into the lid, as otherwise the image produced will be much too dark

to be of any use. Also, because negatives are much smaller than typical

photographic prints, the scanning head needs to be capable of very high

resolutions to capture the full detail: 2,000dpi isn’t an unreasonable level of

detail to expect, but is far higher than the default of regular print scanners.

Photoshop

Elements

Once you’ve scanned in your negatives, all

you need to do is invert the colours: Photoshop Elements or Paint.NET make

light work of this. After that, the process of editing and storing scans of

negatives is just like editing regular prints, with the benefit of

higher-quality images. As a bonus, because negatives are normally provided in

strips, you can scan four or five frames at once, saving a bit of time.

Audio

“If you’re digitising music from a tape

player, life is simpler: attach a line-out to your PC”

Strictly speaking, it isn’t legal to

digitise an old music collection – in fact, it isn’t even legal to rip MP3s

from a CD you own. In practice, however, we’ve never heard of anyone being sued

or prosecuted for doing so.

If you want to do it anyway, you’ll need

the appropriate playback hardware to get your music into your PC. In the case

of vinyl, this means a turntable and an amplifier, with a line-out socket that

can be connected to the 3.5mm line-in jack on your PC. If you try connecting a

turntable directly to the line-in socket on your PC, the output will be so weak

it will be barely audible. If you don’t have such a thing to hand, one option

is to invest in a USB turntable: prices start at around $75, but if you want

the best possible sound and construction quality, you can spend $450 or more.

If you’re digitising music from a tape player, life is simpler: you can attach

a line-out or a headphone socket to your PC.

With the hardware sorted, the next question

is which software to use. Professionally mastered music won’t require any

complicated post-production work, so a simple audio recording and editing tool

such as the free Audacity (http://audacity.sourceforge.net)

application will do everything you need.

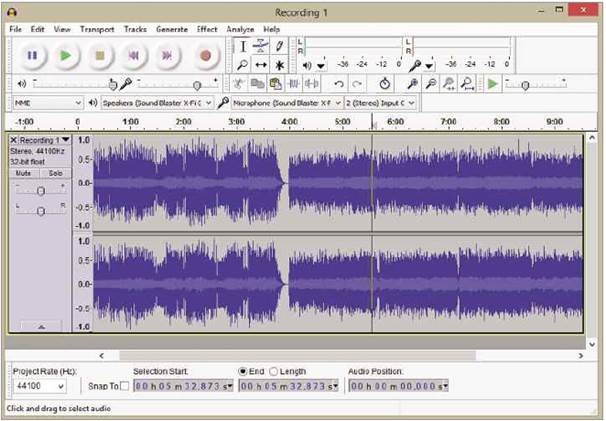

The

free Audacity provides everything you need to turn the music from your old

audio cassettes and vinyl records into convenient MP3 files

The easiest way to proceed is to record

your LPs or cassettes one side at a time, making sure the volume levels aren’t

set too high, as otherwise the sound will distort. Once you’ve made your

recording, you can boost the volume if need be using Audacity’s Normalize

plugin – you’ll find the option in Audacity under Effect | Normalize. This will

amplify your recording to the maximum extent possible without causing

unpleasant distortion.

Next it’s time to split the recording into

tracks. The graphical waveform display makes it easy to spot where tracks start

and finish: click and drag to select a region of the recording, press Ctrl-X to

cut it, press Ctrl-N to create a new Audacity project, then press Ctrl-V to

paste it in, and finally select File | Export to save it in your choice of

format.

Audacity records 44.1 KHz stereo tracks by

default, which are capable of capturing the same level of detail as a CD. This

should be more than enough to reproduce every nuance of a cassette or LP

recording, but predictably enough it produces very large files, working out at

around 9MB per minute of music if you export in the industry standard WAV

format. You may prefer to export files in FLAC (Free Lossless Audio Codec), a

compressed but lossless format that doesn’t compromise on quality but does

offer reduced file sizes. It will play on your PC, can be burnt to a CD, and is

ideal for archival.

The only problem with FLAC is that neither

iTunes nor Windows Media Player can play FLAC media. There are plenty of

third-party programs that can be used to listen to FLAC audio, but if you want

to listen on incompatible devices such as the iPhone, you’ll need to create

lower-quality MP3 copies alongside the FLAC originals. To do this in Audacity,

simply select MP3 from the “Save as type” dropdown.

Whichever format you choose, you’ll have

the option of giving your tracks descriptive names and other information. Take

the time to fill this in, as it will make finding your music in Windows Media

Player or iTunes much easier.

Documents

We’ve focused on archiving audio and visual

media, but what about text? With OCR (optical character recognition) software

you can scan documents such as letters from a solicitor or your household

insurance documents into your PC, and with a few clicks turn them into indexed,

searchable PDFs – a vast improvement on rudimentary filing systems. Such

software is sometimes provided with the scanner, but there are also plenty of

third-party tools such as Abbyy’s FineReader (http://finereader.abbyy.com) and

Dragon OmniPage (www.nuance.com), plus

free options such as FreeOCR (www.paperfile.net).

When you have a lot of documents to work

with, however, the process can be slow. If you invest in a scanner with an

Automatic Document Feeder (ADF), you can pop in two dozen A4 sheets and leave

your PC scanning and converting documents while you get on with other jobs.

Offices with reams of documents may consider a professional scanner such as the

Fujitsu fi-6140Z (web ID: 375679), which can scan 60 pages per minute –

although you’ll pay a whopping $1,800 inc VAT for that speed.

When it comes to saving your scanned text,

it’s hard to argue with the PDF. Adobe Reader may not be universally loved, but

if you’re looking for a text format that will be accessible in 10 years, the

PDF is likely to be it. Besides that, a PDF is searchable, and will retain the original

layout of your document. Some documents are impossible to OCR: handwritten

pages are the most obvious, but damaged documents are another possibility.

There’s still a good argument for digitising them as long as you’re diligent.

The PDF format supports a broad range of metadata, so you can store a brief

synopsis inside each file you save – “letter from Grandma re: Christmas

holidays”, for instance. This way you’ll have a document that can be easily

searched for and referred to without having to retype the handwritten original.