Are the new handwriting recognition systems

any good or just a gimmick?

If you’ve spoken with Siri or pecked out a

few paragraphs using your iPad’s virtual keyboard, you’ll know that

traditional keyboards are no longer the only game when it comes to text entry.

Digital

pens, such as the excellent Livescribe range, are a fast and accurate way to

capture and covert what you write on paper

There are now four generally available

methods for inputting text into OS X and iOS: conventional keyboards remain the

most popular in OS X, while on-screen keyboards are their equivalent on iOS

devices; both now support conversion from voice dictation, and they can accept

handwritten characters either in real time or offline from files created from

recorded writing. Specialist input devices are also available for those with

physical impairments who require more unusual means of controlling keyboards.

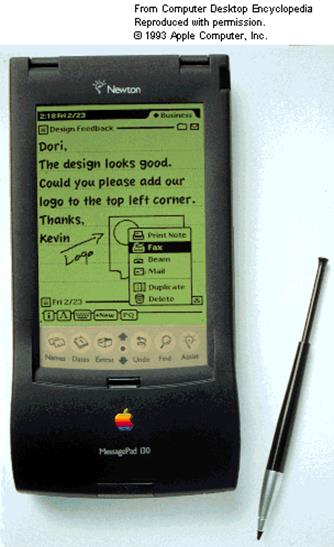

In the heyday of personal digital assistants

(PDAs), such as Apple’s ill-fated Newton (1993-1998), the favored means of text

entry on small screens was real-time or online recognition of text drawn on the

screen using a stylus. Despite substantial research, attaining acceptable

accuracy in recognition required you to form their letters in standard ways and

to enter each individually as if printing them. If you happened to get on with

this approach, recognition was accurate, although most users found errors a

pain, and speed of entry considerably slower than they might write more naturally

on paper.

The

Newton

The Newton’s writing recognition used

directional and spatial ordering of the strokes making up each character, which

is simple to obtain when you write using a stylus on a touch-sensitive screen.

On a Mac, the closest that you can get to the Newton’s handwriting recognition

is the combination of a graphics tablet such as one of the more modestly

priced Bamboo models from Wacom, and Ink, controlled by the System Preferences

pane of that name in OS X, a descendant of that on the Newton.

Although Ink has come a long way since the

rather rigid requirements of the Newton, it still expects you to form certain

characters in specific ways, and to print each character rather than using more

natural flowing or cursive script. If you have any writing quirks, such as

idiosyncratic ‘q’s, you’re likely to find it a frustrating experience. When you

turn on Ink and start writing on your tablet, a floating sheet appears on top

of the active input window and the virtual marks that you’re making on the

tablet appear on screen.

The

Ink

This might work well if you’re fortunate

enough to use Wacom’s Cintiq touch-sensitive display, but when you’re forming

letters on a tablet and they’re displayed not on the tablet but on the

disconnected display, this doesn’t help your hand-eye co-ordination. Perhaps if

you spend a lot of time drawing on a tablet, this peculiar disjunction may

become second nature, but for most users it will be sub-optimal.

Wacom’s Bamboo tablets are relatively cheap

and portable, and may not be out of place in your bag alongside a MacBook Air

or Pro. Standard connection is via USB, but Wacom offers a wireless accessory

kit, which irritatingly relies on its own plug-in USB receiver rather than

built-in Bluetooth. Foreign language support is confined at present to

English, French and German, although the Tegaki Project at tegaki.org offers a

free X11-based Japanese and Chinese character recognition system. iOS devices

have their own touch-sensitive screens, and most note apps now support

handwritten input. However, you’ll need the likes of MyScript Memo if you want

reliable offline conversion to text.

The last year or two have seen several

‘digital pen’ peripherals claiming to capture and convert what you write on

paper. The current leader in terms of accuracy and performance is probably

Livescribe’s offline handwriting system. Unlike Ink, which works online in real

time, most digital pens are intended primarily to work offline, storing

captured jots and tittles for later conversion into text on your Mac.

Livescribe’s

smartpen

The marks that make

up handwritten lettering are fine, and recording them in a manner that allows

reconstitution of the writing has proved be a considerably tough challenge. One

solution has been developed by Anoto in the form of special paper that has

thousands of coded registration marks over its surface, giving it the

appearance of a faint grey stipple. Livescribe’s pens are equipped with a miniature

infrared camera that can see both the marks made by its ink and those coded

marks printed on the paper.

Firmware in the pen records pen-strokes

relative to a co-ordinate system constructed from the coded marks using an

approach similar to that used in land surveying.

Anoto’s coded marks not only provide a

co-ordinate grid on the sheet of paper, but tell the pen on which page in which

notebook the writing is made.

When Livescribe’s software imports a page

of writing, that information is used to reconstruct the contents of the

notebook in PDF files. These can then be passed to a special MyScript add-on

application to perform offline conversion to text. MyScript performs

surprisingly well: given 600 words of technical English written over 30

minutes by a left-handed doctor, 92.2% of words were recognized correctly.

Writing more slowly in a clearer hand, the success rate rose to 97.4%, and

given a bit more care, recognition errors could have become negligible.

Thankfully, making corrections is simple, as a fair image of the handwritten

original can be displayed side by side with the converted text.

Livescribe and similar systems are limited to using their own pens and paper; Livescribe’s

free Desktop software (used to upload pages to your Mac) does allow you to

create your own Anoto-coded paper, but your printer must have a resolution of

600dpi or higher, and even then there are some compatibility issues.

The combination of LiveScribe and MyScript

supports a surprisingly rich range of languages, including most based on Roman

characters, plus Chinese, Arabic, Hindi, Russian and Japanese. The most popular,

including English, are supported in both printed and flowing cursive scripts,

and much in between.

Some competitors, such as IRIS notes

(irislink.com/c2-2193-188/IRISnotes-2-- Digital-Pen-family.aspx) and similar models

from the likes of Staedtler, attempt to do away with special paper, having

their origins in handheld scanners instead. Conversion is available online,

when connected wirelessly to your Mac or iOS device, or offline. Unlike the

rather fat Livescribe pens, those working with plain paper are usually slim line,

but require a second bar-like transceiver positioned close to your writing.

Supporting recognition software may offer training in an attempt to improve

recognition accuracy, but in most hands they don’t perform as well in this

respect as Livescribe’s models.

Much less progress has been made in the

conversion of scanned handwriting to text. Specialist products for use with

forms do work better, and are available from MyScript’s developers at

visionobjects.com, and some high-end OCR products can handle printed writing.

For most users, online handwriting recognition

using Ink and a tablet remains little more than a party trick. As with iOS

devices, you might find it useful for scribbling the occasional note, but it’s

not really a serious competitor for normal keyboards. However, for those who

still prefer to exercise their handwriting skills, a Livescribe pen with

MyScript could prove very valuable indeed.