Plugins

So you can edit pictures, what else

can you do?

There’s no such thing as the perfect photo

editor, and one thing that separates professional tools from the amateur stuff

is support for extensions that add extra functionality, or act as a macro to

achieve particular image effects. Plugins that increase contrast and bleach out

colors have been around for PhotoShop for a lot longer than Instagram

has been in existence.

Plugins

that increase contrast and bleach out colors have been around for PhotoShop for

a lot longer than Instagram has been in existence

Gimp, for

example, has a large and well established library of plugins, including one

that makes it look like PhotoShop. Fotoxx, meanwhile, treats

plugins as simply a custom menu command to launch an external editor.

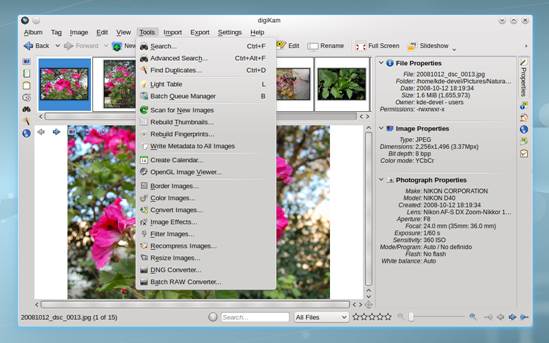

Shotwell and

digiKam come with most of the available plugins already installed – and

many are geared up for accessing photo sharing sites without leaving their

respective environments.

In Darktable nomenclature, every

function and set of image sliders is a plugin. It’s highly extensible, in that

you could add more than the default set of functions, except that there aren’t

any extra ones to download as far as we can see. If Darktable can

capture a large enough audience these will surely come.

When AfterShot Pro was known

as Bibble, there was an enthusiastic community of plugin developers,

both free and commercial. The good news is that these have gone with the

project to Corel, and the forums there are full of homemade packages for

geotagging, framing and generally messing up or improving pics as you see fit.

Outputs

Happy with your editing results? What

about the file format?

There are two questions to address here.

Firstly, what’s the quality of the final photo like? And what can you do with

it?

Gimp, for

example, isn’t yet capable of 16-bit color precision, which is a problem for

professional photographers working in print. It also has an annoying insistence

on working with its own file format, .xcf. Almost everything in Gimp 2.8

was an improvement, apart from the decision to remove other file formats from

the Save as dialogs and move them into an Export menu. There are logical

reasons for this, but it gets in the way of established workflows and

introduces two extra layers of dialog boxes just to output a JPG in the format

it was opening from.

DigiKam

enables the user to export to a large number of file formats and can upload to

and download from various photo sharing sites

DigiKam, meanwhile, is the opposite when it

comes to file formats and is happy to upload download from any photo sharing

site, too. Some of these online plugins are a little unreliable, and the

chances of tags and metadata getting through unscathed are variable. Shotwell

has fewer online plugins, but all the main social sites are covered just fine.

For a RAW converter, AfterShot Pro

has a surprisingly diverse range of output options. There are no direct plugins

for online sites, but you can create everything up to 16-bit TIFFs in terms of

quality and output to ready-made web galleries or contact sheets. It means that

for many shots, no external editor is required to get the perfect picture from

camera to client fast. It’s not without quirks, though – the output dialog is

over-complicated and offers to add more effects, like sharpening, without a

preview.

In the most recent update to AfterShot Pro

the developers also addressed its previous biggest flaw: the default color

balance for pictures is not much more natural, and not quite as eye-poppingly

‘contrasty’ as before. So it’s easier to get great quality shots first time.

And that brings us back to our major

criticism of Darktable – despite the apparent simplicity of the

interface, it’s complex to use, which increases the chances of making a

mistake. You can’t save an image directly after editing it, for example – you

make the changes, go back to the thumbnail view, then find Export Selected

Images. It’s suit some workflows, but makes it inflexible to use.

As far as image quality goes, however, Darktable

is capable of results on a par with AfterShot Pro – if you can master

the controls.

Multithreading & performance

Fancy features are all well and good,

but can it get the job done fast?

Camera sensors are getting bigger, more of

us like to work in RAW formats and bandwidth limitations are no longer critical

for reducing picture quality and size before uploading. Plus, we’re shooting a

lot more photos than ever before.

Image files aren’t getting any smaller, and

our libraries are expanding rapidly. So photo editors are in a Red Queen race:

they need to be more efficient than ever just to seem as good as they were.

AfterShot

Pro: if only it were free software

With the exception of Fotoxx, all of

our software here is multithreaded and can take advantage of more than one

processor core. DigiKam and Shotwell are surprisingly fast at

dealing with large libraries of photos and helping you find the shot you want.

Neither are perfect, though: Shotwell feels a little buggy and slows

down at seemingly random periods, while digiKam’s interface is often the

stumbling block. Opening up a RAW file, for example, means going through a

tedious and old-fashioned import screen rather than going straight to the meat

of the editing tools.

As far as our dedicated RAW editors are

concerned. AfterShot Pro is incredibly fast at cataloguing and editing files,

and designed to get the most out of your workflow.

It’s still a little sluggish at dealing

with picture layers, though, so you’ll likely want to fall back on Gimp

for fine grain editing. Darktable, meanwhile, is fleet-footed in

thumbnail mode, but once you start layering edits onto an image it quirky takes

its foot off the metaphorical gas and begins to get frustratingly slow. Even

zooming in to a shot takes too long (and there’s no slider to show you how far

you’ve zoomed in either).

The triumph of the latest release of Gimp,

meanwhile, is its support for multithreaded processor and – if you’re prepared

to tinker – OpenCL for GPU acceleration, too.

The upshot is that nothing on Gimp 2.8

feels like a chore, so long as you know what you’re doing.