Interface

You’ve got the package, now how easy

is it to get around?

AfterShot Pro

If you’ve used a RAW editor in the last

decade or so, the layout of AfterShot Pro will be instantly familiar to your

eyes. On the left, you have the browsing controls – a file manager, a library

viewer and some settings for filtering and searching for shots. In the middle

is a digital light table that shows thumbnails or zooms to individual pics for

editing.

If

you’ve used a RAW editor in the last decade or so, the layout of AfterShot Pro

will be instantly familiar to your eyes

Over on the right, meanwhile, are the

editing tools. Laid out in a fashion not designed for efficient use of screen

space, but names and ordered in an intuitive fashion such that most photos can

be edited from the default tab, with advanced options for harder work cascading

behind.

It’s not the prettiest or most modern photo

editor, but neither does it look dated or make the user work to find essential

tools. Top marks.

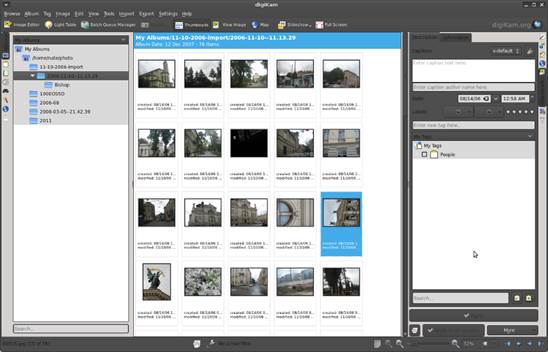

DigiKam

It’s

perfect for someone who handles a lot of images and wants to stay within

digiKam for everything

Few things are more than a click away. It

opens up onto a library manager, and you can rearrange the view according to

title, date taken, meta tags, ratings and more, or switch to a fully-fledged

RAW importer and photo editor. This is also a problem, as by default there are

icons running down both sides of the main frame, and lots of controls to

remember. It’s perfect for someone who handles a lot of images and wants to

stay within digiKam for everything, but if you aren’t going to use the

extra controls, it’s cluttered. Plus some of the cooler features – like the

spinning globe for GPS tagging photos are slightly buggy. The date sorting

panel looks great, but is less usable than Shotwells dull folder tree.

Being a native KDE app, though, it is eminently tweak able.

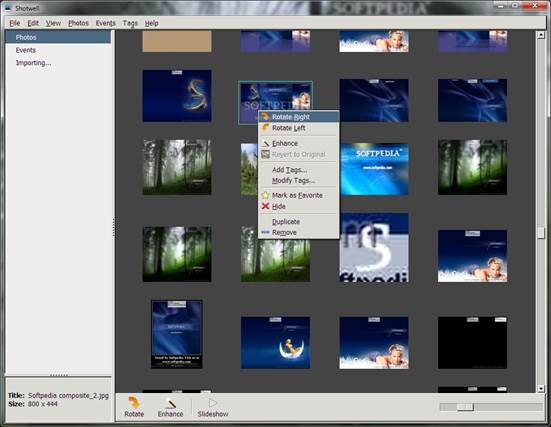

Shotwell

Shotwell

is the next best thing to a dedicated library manager that focuses on helping

you find a photo fast

Now Google’s Picasa is no longer

maintained for Linux, Shotwell is the next best thing to a dedicated

library manager that focuses on helping you find a photo fast. By default, it

sorts images by time taken using a timeline on the right that looks

rudimentary, but is easier to get around than the one in digiKam. You

can also view by tag or EXIF information – although these options aren’t

obvious and require going through the View menu. There’s a one-click photo fix

button, and it uploads shots and albums directly to a vast number of photo

sharing sites. Shotwell is simple, but not yet elegant. The rounded

icons used for folder and album views look slightly out of place, and the

functional sorting column on the left could do with a little love.

Color management

The most important aspect of photo

editing is now commonplace

All of these applications except Fotoxx

can handle full color management. That may not sound important, but is a huge

leap forward for Linux photo editors.

It means they can use a custom gamut, as

laid down according to ICC standards, to alter the way they display colors

according to the monitor’s unique characteristics, the tested color space of

the camera and that of the image which will usually be one of the standard RGB

profiles, such as sRGB or Adobe RGB. This is vital for professional image

editing, as it means the color you see on screen are an accurate representation

of what will be printed. The real credit goes to the Gnome developers for

including simple color calibration controls based on Argylla as a

default control panel setting. It’s easier to fully calibrate a monitor using a

device like a ColorVision Spyder 2 in Gnome now than it is in Windows. The same

applies to Canonical’s Unity environment, which uses the same tool.

KDE is catching up – Oyranos and KCM

are almost on a par with Gnome’s default tools, but require a manual build and

install, while XFCE’s only real option is the CLI-based xcalib tool. Without

setting these up correctly, there’s no point having a color managed editor, as

your monitor won’t be correctly calibrated. Photographers who don’t want Gnome

or Unity do have one other choice, though – Kubuntu includes color calibration

by default, based on the same packages as Unity.

Darktable

The

library view is simple and straightforward, and the editing tools seem

initially straightforward too

The guiding principle for Darktable

seems to be to take the established design of a traditional RAW editor and

simplify it. To this extent, it is a massive success. The library view is

simple and straightforward, and the editing tools seem initially

straightforward too. Then there’s the little flourishes, the swirls that are

reminiscent of a silent movie panel that decorate the black background.

But while it looks simple, Darktable

is a challenge to use. Editing menus are labeled with icons rather than words,

and named unintuitively. Controls are divided into Basic Group, Tone Group and

Explicitly Specified by User. Some of the more commonly used controls aren’t

available, but have to be added from the hidden Plugins menu. Set it up right,

and Darktable is an efficient tool laid out to your way of working. But

for most, the learning curve is staggeringly high.

Fotoxx

It’s

a library management tool that hides its core function

There’s something a little Windows 98-ish

about the interface of Fotoxx that will put most users off trying it.

Not to give it a go, however, is to miss out on some of the wonderful lunacy

that’s gone into the design.

It’s a library management tool that hides

its core function. You get a grey screen that does, apparently, nothing. Only

if you’re very observant will you tap the tiny letter G in a corner that fires

up a file manager with a folder and thumbnail structure that works, so long as

you never need to go up a level. There’s a row of buttons for file functions

and navigation. It’s only when you start going through the file menu options

that the full range of capabilities is revealed. In any other software this

willful obfuscation and confusion of the user would be a sin. But there’s

something joyously quirky about Fotoxx, and it’s hard not to be charmed.

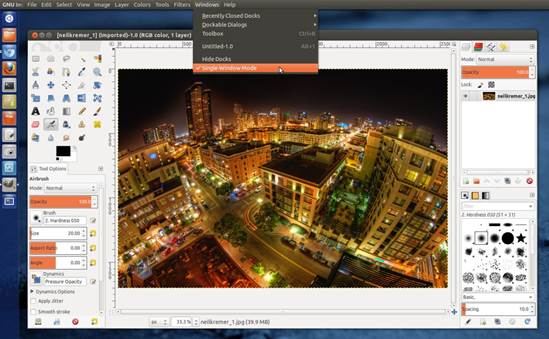

Gimp

Most

of the improvements in the 2.8 version are in the editing engine and the GEGL

framework for plugins

Ah, what hasn’t been written about Gimp

that we can add here? Most of the improvements in the 2.8 version are in the

editing engine and the GEGL framework for plugins that will lead to hardware

acceleration and floating point color control. The basic interface is as

hardcore as ever, feeling as if it’s designed to intimidate newcomers into

submission.

There are some grudging compromises for

those who’ve complained about ease of use. The single window option which locks

dockable toolbars into place is a good start, and you can turn off dialogs that

you don’t need. But Gimp is a place you can do anything from simple exposure

adjustments to masking and cutting out sections of an image to paste elsewhere.

Our only real gripe about the interface is that it still seems to roll a D3

every time it boots up before deciding what docks it will have open. Will there

be layers and histograms? Who knows?