From professional RAW tools to simple

library management, Linux had come a long way, baby..

There’s still a lot of prejudice against

Linux amongst photo enthusiasts and pros, but the time at which our favorite

operating system wasn’t taken seriously for image manipulation is long past.

There may be no Adobe- or Apple- branded software designed for Linux yet and

would we want it if there was? But there are more than enough serious, mature

packages for everything from basic library management to RAW development.

It’s entirely possible to run a

professional studio without the aid of Windows or a Mac these days.

Linux’s

entirely possible to run a professional studio without the aid of Windows or a

Mac these days

There’s such a staggering amount of choice,

in fact, that whittling them down to just six for this roundup involved making

some very tough decisions about what software to include and what to leave out.

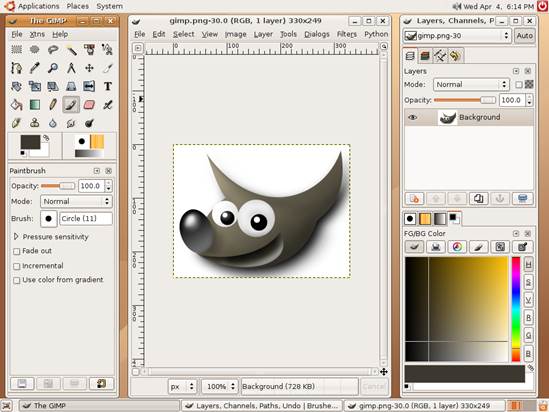

Inevitably, there are some familiar faces. Gimp,

although covered ad nauseam elsewhere, can’t be overlooked when it comes to an

all-round package for most-processing shots. Likewise, you may already know

more than you could ever want to about the Gnome and KDE staples Shotwell

and digiKam but they’re the de facto choice for a reason. Leaving them

out of this roundup would be to not consider the very best.

The real controversy, in fact, is whether

or not to include Corel’s AfterShot Pro – new Bibble in

the roundup. It‘s the gold standard for RAW image editing on Linux, but it’s

also closed source and not terribly cheap either, at $59.99 for the full

version. It has been updated since we last looked at it, though (LXF156),

so we’re going to revisit it at the expense of a truly FOSS alternative. It

feels wrong, but it’s the right thing to do.

Disagree with our choices? Email us at www.linuxformat.com/forums.

Casual or pro?

Who’s the software aimed at, and

should it matter in terms of ease of use?

There’s any array of audiences catered for

in our six candidates, and intentionally so, but none of these packages is

short on features. It’s more about the way they’re presented and interact with

one another.

So, if you’re looking for something simple

just to manage your photos and remove a bit of red eye, then distribution

stalwarts digiKam and Shotwell should be amply suited to your

needs. Both focus on the essentials of a photo manager, and while they have

in-built editors neither are prescriptive of force you to use them.

AfterShot

Pro has a wealth of professional-level tools that are easy to use

Shotwell,

especially, is designed for simplicity of use with the same kind of bare

minimalism that developer Yorba has injected into its excellent email client, Geary.

Open it up and you get photos on the right, and sorting options on the left,

with little else between. The image editor is almost app-like in its

simplicity, though – there’s a one-click Enhance button, which spruces a pic up

before you publish it to the sharing site of your choice.

DigiKam is

far more fleshed out, however, and full of options and features for the

tinkerer. It’s difficult to say who digiKam is for, though. The Library

tool is exceptional, allowing you to sort by date, tag, facial recognition and

even a ‘fuzzy search’ that tries to match general shapes to an existing image –

you’re invited to ‘sketch’ the shape you want to find in a blank box and digiKam

will try to find it.

Aside from the slightly variable results

from fuzzy searching and face matching, though, digiKam can prove to be

a bit intimidating for the very casual user, without containing powerful enough

editing tools to please the professionals.

AfterShot Pro, as the name suggests, is a proper tool for proper tool for proper

photographers. It has a sophisticated library manager, a reasonable image

editor and arguably the best RAW development tools of any software on any

platform. It’s also not expensive when compared with the likes of Lightroom

or Aperture, although having said that it isn’t cheap enough for the

faint-hearted.

Darktable is

designed purely for handling RAW files, but is better suited in our opinion to

the enthusiastic amateur photographer than the pro. It’s got an incredible

number of features, and can do everything that AfterShot Pro does, but

it’s infused with the spirit of open source and too infinitely tweakable to fit

comfortably into a serious workflow. Wrestling every picture into perfection is

fine if you only have two or three to fine tune – not if you need to process

hundreds of shots in a day.

Gimp,

meanwhile, is still overwhelming for the novice despite a recent makeover.

However, lack of competition for picture editing functions, like a clone brush

and layer control, means that it’ll find its way into most photographers’

toolboxes, whether you’re just brightening party shots taken on your phone or

looking to create artwork for high street advertising campaigns.

Photo management

Lots of images to look after? Which

one excels at it?

Most of us start off managing our image

libraries using a standard file manager and some cleverly named folders. Some

of us stick with that through our entire careers. But why complicated things

when you can double-click on ‘Christmas 2012’ and Nautilus or Dolphin

et at will throw up a page full of brows able thumbnails?

Gimp

is a pure editor, and wisely eschews trying to do too much

With one notable exception, all of our

candidates have some form of library management in their design. Gimp is

a pure editor, and wisely eschews trying to do too much.

Library management is at the heart of Shotwell

and digiKam, and both do the job well. DigiKam will sort your

shots by any combination of folder, date and EXIF o tag you want, although the

interface can be a bit cludgy once you move away from the file tree.

Shotwell is

a little more limited, as it sorts everything by date first which can be

problematic if you don’t tag you shots with subject information.

AfterShot Pro, meanwhile, has a very sophisticated library function that allows

you to sort photos according to just about any parameter. Unfortunately, it’s

let down by an import function that is overly complicated, and won’

automatically watch folders for updates, so the in-built file browser is better.

That’s probably the reason why Darktable’s library management reflects

the file structure on your hard drive – it’s simple and lets the app get on

with generating fast, brows able thumbnails.

Fotoxx, again, displays its weirdness here.

It should be a library manager, but operates more like a file browser, in which

there’s no obvious way to go up a level. Odd.