Remember thin client computing? Well, it’s

back again, and it’s faster and cheaper than ever

If you don’t remember the last time thin

client made the news, then here’s a brief intro. Back in the days when

computers were big and expensive, each one had several terminals attached to it

so lots of people could use one computer at the same time. PCs (personal

computers) put a stop to that in many situations because they became so cheap

you could put a computer on a desk for the price of a terminal. Then we got

networked PCs running software held on a server and suddenly the distinction

wasn’t so clear any more.

Server

on the right, terminal on the left

‘Thin client’ became the preferred term for

terminals that had very little processing power of their own and no locally

installed applications. They did little more than display images created on the

server. ‘Fat client’ referred to PCs that could run their own software, but

often ran networked stuff in a business setting. For example, you might run an

office suite and a browser on your PC but log into Sage or some other

enterprise management package running on the company server.

Thin client computing has never totally

gone away, though. They may be pretty rare in offices these days, but thin

clients live on as PoS (point of sale) terminals in shops, and as control

consoles in industrial processes. And they are sometimes used in education,

libraries, computer kiosks and other situations where people want simple,

cheap, secure access to basic computing. In my case, I’m experimenting with a

system that will eventually go into a social enterprise hub in Llangollen.

The

extended case keeps the SD card secure

LTSP (The Linux Terminal Server Project

- www.ltsp.org) exists to meet that

need. LTSP servers are usually just desktop PCs with a lot of memory and plenty

of hard disk space. Until recently, LTSP terminals were usually either old

terminals from commercial mainframe computers or just old PCs given a new lease

of life as thin clients. But now we have the Raspberry Pi to play with.

BerryTerminal

BerryTerminal (berryterminal.com) is a minimal Linux

distribution designed to turn a Raspberry Pi into a low-cost thin client, which

will connect to any Linux distro running LSTP. Like all Pi projects, it’s come

a long way in a short time, and there are almost daily updates.

Raspberry

Pi safely boxed

We’ll look at the server setup first,

though, because then you can use that to create the BerryTerminal SD card.

LTSP Server Hardware

There’s loads of information about LTSP on

the LTSP website at wiki.ltsp.org. Specifying a server is not straightforward;

it very much depends on what your users will be doing, and how many of them you

have. The wiki pages suggest that if you have a few people playing simple

games, a few browsing and a few using Libre Office, a single 2GHz processor

should handle 20 users. I’m pretty skeptical about that, and given that you can

get a less than state-of-the-art dual- or even quad-core device pretty cheap

these days, I’d aim a bit higher.

Raspberry

Pi mounted on the rear of the monitor and cables coiled up neatly

The LTSP wiki gives a formula for

calculating how much RAM you need and comes up with 4GB for 20 users.

Elsewhere, though, I’ve read users suggesting 1GB for the server itself plus

500MB for each user if you are using a graphical desktop, watching video and

visiting Flash encumbered websites.

Each user will get their own ‘Home’

directory on the server, so plenty of disk space is essential, and if you want

to avoid being lynched by disgruntled users, make sure you have a RAID 1 system

in case a disk fails!

For 20 or more users, you really need a

gigabit network interface from server to network switch, though 100Mb is okay

for each terminal. Most of the documentation assumes you have a server with two

network interfaces: one to link the server to the internet, the other to handle

the clients. In a home or small office you can use a single NIC or on-board

Ethernet and a domestic router. As we’ll see later, a separate network switch

is a big help rather than relying on Ethernet ports in the router itself. For really

big networks, multiple server setups can be used to share the load.

My tested machine currently is a

three-year-old, dual-core Dell Inspiron with 2GB of RAM, but I’m only running

one client so far. With LTSP used in quite a few schools, a lot of references

are to Edubuntu, but I did a fresh install of Lubuntu, which has the LXDE

desktop as standard. The Raspberry Pi client won’t handle Ubuntu’s default

Unity desktop, and I’m not keen on the fallback Gnome. LXDE is light and fast.

There are a couple network things to deal

with before we get into LTSP itself.

DHCP

Dynamic Host Control Protocol (DHCP) is the

system used to hand out IP addresses on a network automatically. In a simple

home system, the router functions as a DHCP server and you don’t have to think

about it, but it’s an issue with LTSP. The LTSP server gives IP addresses to

each of the clients so they can communicate, but if it tries to give out an

address already used by your router you have a problem.

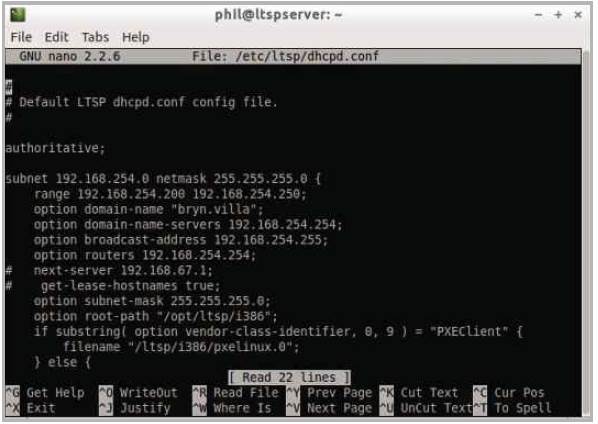

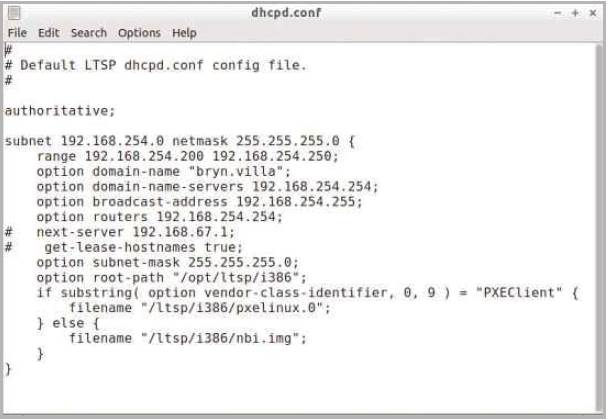

Configuring

DHCP in Nano

The first step is to find those old login

details you got when the router was new and log into it. Somewhere in the menu

system you’ll find details of its DHCP server settings. IP addresses on home

networks are generally 192.168.xxx.yyy, where xxx and yyy can be any number

from 0 to 254. You will probably find that the router uses a limited range of

numbers in the last group for DHCP. On mine it’s 0-199. 254 is the router’s own

address and three others are reserved. 200-250 are available for LTSP to use.

Make a note of your router’s settings. You may well find the range is

adjustable, in which case adjusts it as you wish.

Configuring

DHCP in Leafpad

Next go to your server’s network settings

and set a fixed IP address. This usually means unticking DHCP. Chose a number

outside the range used by DHCP on the router (in my case, I use 200).

LTSP Server Setup

You can add LTSP to any distro using the

normal package managers or one of the newer application installers. The snag is

if you enter ‘LTSP’ in the search you’ll get a huge list of applications and

libraries and not much indication of what’s really needed to get started. There

is an easier way, but it involves a bit of typing. Open a terminal and enter:

sudo apt-get install ltsp-server-standalone

(Or if your distro allows it, login as root

and dispense with ‘sudo’.)

This will drag in a whole load of related

applications and libraries, saving you the bother. Now we have to configure

LTSP server, and that means editing a config file by hand. You need to run any

text editor with root privileges, my preferred method is to open a terminal and

run ‘sudo nano’ followed by path and file name.

Nano is a basic text editor that runs in a

terminal session. If you’re using LXDE, then ‘sudo leafpad’ opens a more modern

editor. In this case the file that needs attention is dhcpd.conf so the command

is:

sudo nano /etc/ltsp/dhcpd.conf

Before you start messing, back up this

file. I usually just add .old to the file name so if I screw up I can find it,

delete the .old and have the default file back.

As you might guess from the name and path,

this file controls how LTSP uses DHCP. Referring to the sample file here, you

need to change the first three sets of numbers of the subnet to match your IP

address and set the last to 0.

Set range outside the DHCP range dished out

by your router. Domain name is optional. Leave it on default if you want. Domain-name-servers

have to be the same as the IP address of your router.

Set option broadcast-address so the first

three sets of numbers are the same as the subnet setting and end with 255.

Option routers should be the same as the

option domain-name-servers. All other settings can remain the same. Save the

file with its original filename. Restart the DHCP server with:

sudo service isc-dhcp-server restart