One of the better things to emerge from the

aftermath of any massive data breach is the research value of the data that's

sold on the dark market (and often published for free somewhere within the

hacker underground soon after). I'm talking about the likes of the Yahoo breach

earlier this year, which left 400,000 plain-text passwords exposed; the

Linkedln breach, which published 6.5 million unsalted SHA-1 hashed passwords;

and the Sony PlayStation Network breach with 100 million records, including

login data, stolen. These three together account for a pretty impressive

password research pool. By analysing the password databases that were stolen,

it's possible to determine the most commonly used and therefore the most

insecure passwords out there.

How

Secure Is Your Pin?

Most are insecure by dint of being so

common that they're included in every dictionary attack, even though they're

not dictionary words. The 14 most insecure passwords have remained consistently

so over the 20-plus years that I've been in the IT security business (on both

sides of the fence) - namely password, passw0rd, 123456, 12345678, 111111,

iloveyou, qwerty, dragon, pussy, letmein, abc123, baseball, football and TrustNet.

I'd be absolutely amazed, not to mention disappointed given the number of words

I've thrown onto paper and the web over the years, to discover any regular

PCErTA reader using any of these; you obviously know better than that. But

what's the situation when it comes to PINs?

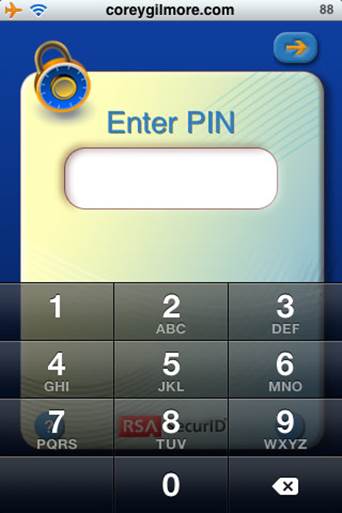

Personal Identification Numbers (PINs) were

once solely the province of hole-in-the-wall cash machines, but the advance of

technology, along with a superficial nod towards better security in all things,

has changed that. Now we need to provide PINs when making credit card payments,

when banking online, to access our smartphones and tablets, and even with some "ultra-secure"

USB memory sticks that come with a PIN entry-code system built in. The trouble

with PINs is that they suffer the same problems as passwords when it comes to

their popularity-versus-insecurity ratio.

The

trouble with PINs is that they suffer the same problems as passwords when it

comes to their popularity-versus-insecurity ratio.

A security company analysed more than three

million PINs, extracted from the same kind of stolen password files wherever a

password was found that was a four-digit number, it was extrapolated that the

usage patterns of that password would apply equally to the choice of a similar

PIN and it discovered that the top 20 most common PINs were used by 27% of all users.

Given that most, but not all, PINs are four-digit codes, you already have a one

in 10,000 chance of guessing it correctly first time, and that reduces to 1 in

3333 given three guesses, which is fairly common in banks and mobile networks

alike. All of this is based on the PINs lying in the range of 0000 to 9999, but

the odds of a successful guess are hugely improved if that range is

considerably shrunk, which is where the popularity problem comes into play a

staggering 11% of the PINs analysed in that Data Genetics study were simply

1234, closely followed by 1111 at 6%, and when you throw in 0000 you have 20%

of all PINs out there.

All these PINs should be firmly relegated

to "do not touch with a barge pole" status, since they're so lazy and

stupid as to be laughable in terms of security. This statistical analysis

becomes even more worrying once you realise that the 426 most popular codes

account for 50% of the total PINs in use. Among the ones to avoid would appear

to be any number starting with 19, since these are also birth years, and hence

easy for the user to remember (and easier for the bad guy to guess) than

anything truly random. What's more, the later the 19xx number, the more likely

it is to be in use, since those in the first few decades of the century are

dying from old age. But using birthdays for PINs isn't restricted to years, so

codes built from numbers between 01 and 12 and 01 and 31 for the first and

second duets (which depends on whether you're European or American) should also

be avoided.

Don't try to be clever by choosing what

appears to be another random code that's nothing of the sort. The study found

that 2580 was very popular 22nd in the most-used list - because those digits

are all aligned in a top-to-bottom column on cash machines and smartphone

keypads. This highlights the biggest mistake people make when choosing a PIN,

and that's thinking that "easy to remember" has to equate to

something that will jog your memory. Truth be told, if you're using any PIN (or

password) that relates to something else in order to make it easier to recall,

then it's also going to be less secure than something truly random.

The least popular PIN in the Data Genetics

analysis, right at the bottom of the list with less than 0.001% usage, was

8068. (Now the study results are out I imagine it will shoot right up the

charts and become much less secure by virtue of people thinking nobody would

guess it.) The point I was about to make, before getting distracted by 8068, is

that random numbers are just as easy to remember. We're only talking four

digits after all, and after a few uses such a PIN becomes second nature.

The

least popular PIN in the Data Genetics analysis, right at the bottom of the

list with less than 0.001% usage, was 8068.

Of course, the same advice applies to the

reuse of passwords and that is, simply, don't. It's tempting to have the same

PIN, the same password, for everything in a world that's drowning in access

codes, but that's sheer folly, since breach after breach has arisen from access

to one service opening up access to a host of others as a consequence of such

reused credentials.

So if you have to have dozens of different

four-digit PINs, surely this blows apart my "random numbers are just as

easy to remember" theory? Well, kind of. However and I'll admit that this

remains a contentious issue within the IT security fraternity this is where

password managers or "vaults" come in. Provided you choose your

solution wisely, taking into account the level of encryption applied to your

data store and the location of that storage, there's no reason why these

shouldn't be secure. As long as your master password is strong, by which I mean

at least 12 digits including alphanumeric, both cases and special characters,

it's a more secure method than reusing that same strong password across all

your software, sites and services. Remembering a long and complex master

password isn't hard, not if it's all you have to remember. Use random PIN codes

after you've ruled out those common "do not use" digit combinations

stored in this way and your PINs should be as safe as your passwords.