Get your house in order

My advice to anyone who’s seriously worried

about this new development – which, at the time of writing, is only available

to those who’ve expressed an interest in beta testing, with no firm date for

when it will to live – is to stop using Facebook altogether or revise your

privacy settings. In fact, the imminent arrival of the new search facility is a

good excuse to double-check all your settings and get your social privacy house

in order. Start with your timeline settings, and in particular the “Who can see

things on my timeline?” setting. If you select the “View As” option, you’ll be

able to see your timeline as the public sees it; this can be an eye-opener to

users who haven’t paid much attention to their Sharing settings.

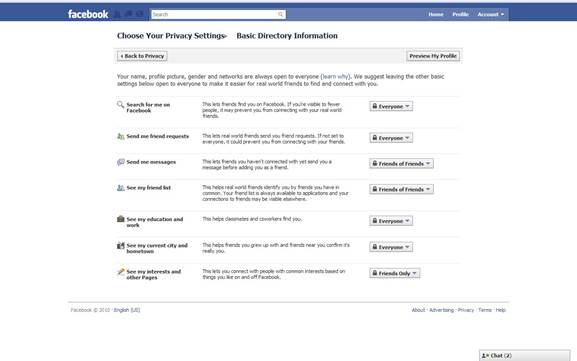

The

Privacy Settings page lets you determine who can see your future posts and

allows you to revise posts you’re tagged via the Activity Log page

The Privacy Settings page lets you

determine who can see your future posts and allows you to revise posts you’re

tagged via the Activity Log page. You can also limit the audience for posts

you’ve previously shared with friends of friends, or the general Facebook

public. You can edit the basic information from the About section and remove or

restrict anything you don’t want showing up in searches. I have my date of

birth listed, which might seem insecure from a phishing aspect, but this

information is restricted to only my friends on Facebook. If I don’t trust my

friends with that information (which is pretty easy to find through other means

anyway) then maybe I should be more careful with whom I make friends.

Likewise, you can go to your Photos section

and hide individual photo albums. The point is that, as a rule of thumb, the

View As option not only lets you see what the public sees, it also makes you

aware what data will be viewable via the Graph Search function.

So the real problem with Facebook Graph

Search isn’t one of privacy but rather that it’s just too good at doing what

it’s been designed to do. The bottom line is that nothing that can’t be viewed

by someone who asks for that information right now will be revealed by this new

search engine. The only nasty surprise awaiting most people is just how much of

their data is already viewable by all and sundry.

Before I leave myself open to too much

criticism from those who think I’m becoming some kind of Facebook shill, I

should stress that I think Zuckerberg ought to reinstate the ability to opt out

f search altogether.

If, as has been claimed, only a

single-digit percentage of the overall membership did so previously, it seems

highly unlikely this would have a negative impact on the functionality of the

new search interface, unless there were a mad rush of opt-outs. That’s equally

unlikely, given how well Facebook Graph Search works.

Facebook privacy notices are nonsense

While we’re on the subject of Facebook

privacy, you’ve probably seen a rash of posts – by people who ought to know

better – that claim to exert copyright on everything they post and threaten

legal action against anyone who uses their posts without explicit written

permission. The exact wording of these “copyright notices” varies, although

some are simply cut-and-pasted templates, which is even more annoying.

Facebook’s

Terms and Policies page keeps you up to date with everything privacy-related

They all appear to start with the same

words: “In response to the new Facebook guidelines, I hereby declare that my

copyright is attached to all of my personal details, illustrations, paintings,

writing, publications, photos and videos, etc”. They also seem to share a

conspiracy theory about “the government using or monitoring this website”, as

evidenced by the inclusion of statements insisting the notice applies to all

organizations. Facebook itself is also singled out, with quasi-legal wording

that purports to prohibit the social network from any commercial use of content

posted by the member concerned.

Whether such notices are in response to

some of the more alarmist rumors and media reports following the Facebook Graph

Search announcement or just the usual viral cycle of such nonsense. The fact is

they’re all a total waste of time – not merely their own time spent posting

them, but also my time and the time of everyone else who ends up reading them

in their feed.

Why? For one thing, there’s the small

matter of the terms and conditions of use that you agreed to when you joined

Facebook. There’s no opt-out clause, and simply posting something that says you

don’t agree with those terms and conditions doesn’t cut it, since the act of

continuing to use Facebook is legal confirmation that you’re bound by all the

terms and conditions in place at the time of use.

As always, the devils is in the detail,

and, rather than moaning about privacy policies and legal terms, you should

read the relevant documents in full and then decide whether the benefits of

using the service outweigh the perceived privacy handicaps. You’ll find them

all on Facebook’s Terms and Policies page (www.facebook.com/policies) and,

perhaps a little surprisingly, you won’ need to be a lawyer to understand them.

Yes, I write down my passwords

A new survey by YouGov is being spun – or

at least that’s how the press release reads – to show that workers still aren’t

implementing secure data protection practices. I don’t see this as all bad

news, however – in fact, quite the opposite.

The headline statistics from the survey,

commissioned by technical training company a, show that 18% of the 1197 workers

questioned didn’t have passwords or PINs set for all their work devices

(including laptops, tablets and smartphone), and 23% of those who had shared

them with someone else, while 21% had written them down.

The accompanying press release insists this

highlights “major cyber security flaws”, which are “contributing to corporate

cyber security risks.”

Visit

your Facebook Activity Log page to discover ways to deal with unwanted entries

While I can’t argue against the

contribution made by such password folly to data insecurity, I’m not entirely convinced

the research is a doom-and-gloom revelation.

Simply turning those numbers around

suggests that almost three-quarters (allowing for “don’t knows”) of those asked

do protect all their devices and don’t share the passwords.

The main problem with research such as this

is that it’s never really so black and white: if I were asked, for example,

whether I write down my passwords, my answer would be a resounding “yes, I do”.

Of course, I don’t write them down on a Post-it note stuck to my monitor but rather

within a well-encrypted, locally stored database. Similarly, I’d be inclined to

say I also share my passwords, as a copy of that encrypted database has been

deposited with a third-party cloud provider to enable me to access it from any

device, at any time.

I accept that doing both things slightly

increases the risk of password disclosure above what it would be if I kept them

in my head, but not by very much, since the data itself is well encrypted, and

much more secure than it would be when stored in a Post-it note format.

The software I use ensures that my complex,

long and very strong master password is never transmitted from whatever device

I’m using at the time, with all the decryption and encryption being performed

locally. The Agile Keychain data format used is capable of withstanding

sophisticated attack methodologies, and the supposed weakest link in the chain

– the third-party cloud service – adds yet another layer of encryption itself,

so my encrypted data file is encrypted again.

I’m not suggesting YouGov’s survey is

pointless, because anything that helps hammer home the

security-in-the-workplace message is worthy. I just think we need to be a

little more cautious when it comes to interpreting such numbers as negative.

We should rejoice in the fact that so many

have received and understood the security message, then look at how we can help

the small minority who haven’t. That includes their bosses, the people charged

with both determining security policy and applying it.