The return of @font-face

This worst-case scenario hasn’t come to

pass, however, because the rise of HTML5 made the various browser developers

keen to extend capabilities. As a result, web fonts returned to the agenda. In

2007, Microsoft submitted its EOT format to the W3C for open use through a

newly restored @font-face rule in CSS3.

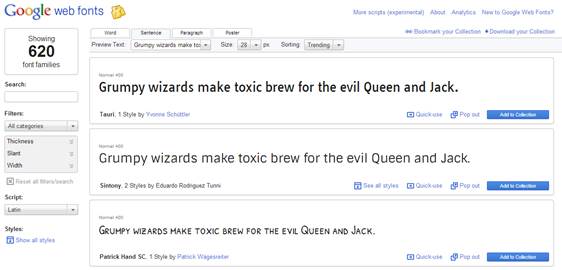

Google

Web Fonts will deliver your choice of open-source typefaces directly to your

site visitors with a single line of code

Naturally, having a single web font format

would be far too simple for the world of IT (although the W3C’s new Web Open

Font Format – WOFF – may eventually come to play this role), so none of the

other browser developers actually added EOT support. They have added support

for other CSS3-approved font formats, though, such as TrueType, OpenType and

Scalable Vector Graphics. This means that, as with web video, a designer needs

to provide web fonts in all of these formats and then load them up

appropriately as required.

Thankfully, though, most of the pain has

been taken out of this process by online services. An excellent example is Font

Squirrel, which searches through a wide range of open-source web fonts that can

be downloaded, arranged into categories such as Calligraphic, Display and

Grunge. You can even download your chosen face as a font kit, which provides

the typeface in multiple formats, along with the necessary CSS code to deliver

them correctly to each browser. Best of all, Font Squirrel lets you upload your

own typefaces to generate font kits, enabling you to deliver any font yourself

(assuming that the font license permits such use).

Several services go a stage further and

will deliver their own range of open-source fonts directly to your end users

through a super-efficient content delivery network.

Here, Google is leading the way for free

handling (www.google.com/webfonts),

with more than 600 font families and more being added all the time. All you

need do is select which fonts you want to use, add them to a collection, choose

whether or not you need an extended character set, and then pick up the one

line of custom code you need, for example:

<link

href=’http://fonts.googleapis.com

css?family=Fruktur’

rel=’stylesheet’

type=’text/css’>

Google also provides advice on deploying

your fonts, and lets you download them for local installation, which is

important if you’re designing your site in Photoshop or producing a brand

identity across both web and print. Google is also trialing web-font subsetting

and styling, which will help make the most of short sections of eye-catching

text, say in banners, buttons or adverts.

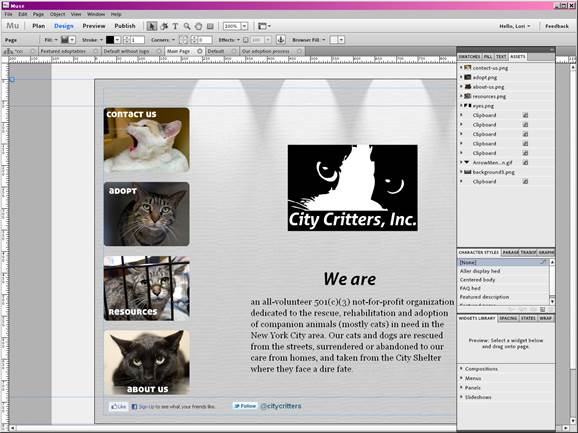

New

authoring applications such as Adobe Muse are beginning to turn web design into

a typographically rich wysiwyg medium

Google Web Fonts has plenty going for it,

not least it popularity, which should ensure many common fonts are already

cached by your visitors’ browsers, further boosting download performance.

However, there are concerns about the quality of some of its open-source fonts,

especially for use in long sections of body copy.

For professional use, the Typekit service,

which was acquired Adobe in 2011, provides a wider range of fonts – currently

almost 900, with 1,000 more Monotype faces in the pipeline – from a wider range

of foundries and designers, all carefully optimized and hinted for web use. It

also provides the most attractive front-end for finding the perfect font,

provides useful information about each typeface, and lets you quickly try out

your own text online and see how your font will render at any size on any

browser (right back to IE6 on Windows XP).

The major downsides of Typekit are that you

don’t get direct access to the fonts for downloading, and you have to pay if

you want to move beyond its free personal usage offer of one website/two

fonts/25,00 page views per month. However, the pricing is reasonable, with

unlimited fonts on only $50 a year. If you’re a member of Adobe’s Creative

Cloud, this is included in the package.

For

professional use, the Typekit service, which was acquired Adobe in 2011,

provides a wider range of fonts

As an alternative, Adobe has made more than

500 screen-optimized, open-source fonts from the Google Web Fonts collection

available for free delivery via its Typekit infrastructure through its new

Adobe Edge Web Fonts service. The online front-end for selecting Edge fonts and

generating your code is currently pretty well non-existent, and it may well

stay that way, too. The real advantage of the Edge Web Fonts service is that

Adobe is integrating them directly into its new range of web-authoring

applications: within the latest version of Muse, for example, you can already

visually select from a range of Edge Web Fonts and apply them to text, just as

you would in a print-orientated design package.

With near-universal browser support for

CSS3’s @font-face rule across desktop and mobile devices; low-cost and free

third-party delivery of a huge range of open-source and web-licensed typefaces;

subpixel anti-aliasing on increasingly high-DPI displays; and now simple

WYSIWYG as well as code-based authoring, it looks as if everything is finally

falling into place. Fifteen years after IE4 first offered web-font support, it

really is possible to deliver fantastic web type to just about everybody. It

should mean the web can become a design medium worthy of the name, and Georgia

and Verdana may finally enjoy a long overdue and well-deserved retirement.