Core fonts

Until these various problems with web font

delivery were sorted out, it was important to do what you could with those few

fonts you could assume the end user would have installed – always remembering

to provide fallback positions in case they didn’t – and here Microsoft again

led the way with its “Core fonts for the Web” project. This was a package of

TrueType fonts – Andale Mono, Arial, Arial Black, Comic Sans MS, Courier New,

Georgia, Impact, Times New Roman, Trebuchet MS, Verdana and Webdings – that was

freely available for both Windows and Mac. Unfortunately, these fonts didn’t

become universal (which immediately meant you shouldn’t use Wingdings, because

it couldn’t degrade gracefully to another front) and, in any case, could hardly

claim to be extending the boundaries of web typography. Arguably, it set

standards back, with Comic Sans being notoriously prone to misuse – for

example, in CERN’s presentation regarding the discovery of the Higgs boson.

Microsoft

deserves great credit for commissioning font designer Matthew Carter to produce

these new screen-optimized faces

There were two honorable exceptions,

however, in Georgia and Verdana. Microsoft deserves great credit for

commissioning font designer Matthew Carter to produce these new

screen-optimized faces, and Carter deserves the same credit for realizing that

he needed to start from hand-crafted bitmaps and then apply advanced hinting to

match font outlines to the available pixels, rather than from simple outlines

that would rasterize well.

As a result, these fonts change shape

considerably to render optimally even at the smallest sizes – where strokes are

a single pixel wide – but still manage to maintain an overall identity. Their

large x-heights, their clear distinguishing between similar characters such as

1, l and I, and their expansive spacing that boosts legibility and long-form

readability are all reasons why these two web-font workhorses became almost

universal across the PC, Macs and billions of web pages.

Progress… and problems

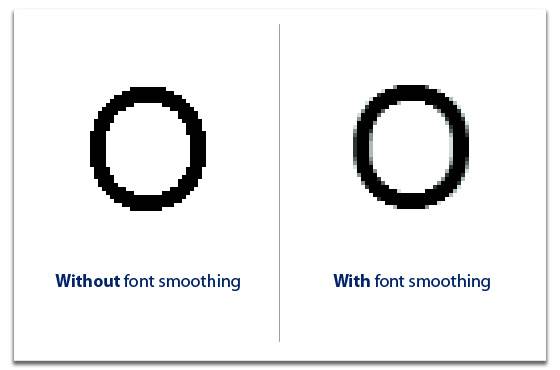

Georgia and Verdana do a superb job of

making the most of the least number of pixels, but a clear need remained for

improved type rendering. Screen delivery differs from paper in this regard,

because you can vary the grey scale of each pixel through anti-aliasing to simulate

the partial presence of a letterform, fooling the eye into an impression of

greater resolution. The launch of Windows XP in 2001 with its anti-aliased

rendering was a huge step forward, although web designers were still

constrained by the knowledge that Windows 98 lacked such advances.

Georgia

and Verdana do a superb job of making the most of the least number of pixels,

but a clear need remained for improved type rendering

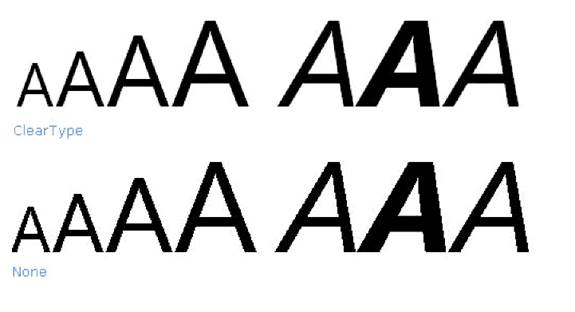

The next trick was to vary the separate

red, green and blue elements that make up each pixel to produce “subpixel”

anti-aliasing. The 2007 Windows Vista made this ClearType rendering the new

default, another red-letter day for web typography.

ClearType

is a form of sub-pixel font rendering that draws text using a pixel's red-green-blue

(RGB) components separately instead of using the entire pixel.

The font-smoothing effect of subpixel

anti-aliasing isn’t perfect, since it works only along the horizontal axis and

can produce undesirable color fringes, but it does dramatically improve the

capability of a screen for high-quality type over and above the ever-increasing

pixel density.

Font

smoothing – An anti-aliasing algorithm used to minimize

distortion of fonts on monitors

However, there was a new showstopper in

sight. Back in my 2002 book I assumed that support for font embedding would

soon become universal, since it only required Microsoft to open up EOT, and

Netscape and Opera to support it. That proved naïve, and the success of Firefox

and Safari meant the proportion of end users who could see web fonts began to

fall. With the dream of universal delivery fading, fewer designers bothered to

embed EOTs, and in 2003 Microsoft stopped developing WEFT altogether (although

it’s still available). With the launch of CSS 2.1, support for @font-face

embedding was dropped entirely, and it looked as though the web had made its

choice – the typographic possibilities for the most important communication

medium since paper would shrivel to a choice between Georgia and Verdana.